This talk was delivered today at Davidson College at its Annual Teaching Showcase

Thank you for inviting me to speak to you today. I’m particularly pleased to be at a Center for Teaching and Learning, since I spend a lot of time muttering angrily about the powerful narratives I notice in circulation these days, narratives readily promoted by politicians and business people, by education reformers and education entrepreneurs, that teaching and learning somehow aren’t actually of interest to educators (professors care only about their personal research, so the story goes) and that learning does not really happen in formal educational institutions these days – neither sufficiently nor efficiently.

I’m fascinated and frustrated by these narratives as by and large they tend to utterly ignore the present and the past. In particular there’s an outright erasure if not retelling of the history of education and the history of education technology.

It’s hardly a surprise, I suppose. Ideologically if not geographically centered in California – the land of gold and opportunity, and of course, Hollywood – Silicon Valley, one of the major forces behind these narratives, likes to carefully craft, re-invent, and mythologize its past. I’ve heard education technology entrepreneurs claim, for example, that education has not changed in hundreds of years; that before MOOCs, the last piece of technology introduced into the classroom was the blackboard; that education has been utterly “untouched” by computers; that the first time someone in education used the Internet for teaching was 2001.

I want to talk to you today about the history of education technology, not just to point out that “OMG! He got the date totally wrong!” (2001 is totally wrong. Totally.)

I think that this purposeful mis-remembering and mis-telling of the history of education technology reveal great flaws in the project of ed-tech writ large, not to mention flaws in the stories we tell about the supposed future of teaching and learning.

Education technology promises access and efficiency. It promises mobility and engagement. It promises freedom and agency. It promises a lot of things – good marketing campaigns always do. But in practice, education technology has never been able to live up to all the hype. And that isn’t simply because the promises were too grandiose; it is also because the history of education technology is systematically being forgotten, if not re-written.

Just this week, I saw a story that pointed to Stanford professor Patrick Suppes as the “intellectual father of personalized education.” Suppes began work in the 1960s on computer-assisted instruction – early “drill-and-kill” programs. To call him the father or the first, is to ignore decades of work that came before – that, one might note, did not emerge from Silicon Valley. It certainly overlooks the claims that Rousseau made in Emile in 1762. But Silicon Valley insists upon the “new,” the innovative. It’s convinced, in this example as with MOOCs, that it’s somehow "the first.

I’m working on a book called Teaching Machines, which looks at the history of education technology beginning in the early twentieth history and specifically at what I call “the history of the future of education” – the stories we have told and still tell about what we imagine technology will do for teaching and learning.

![]()

My academic background is in the study of literature and folklore, not in the study of engineering or education. As such, I am interested in cultural imagination and in stories. I’m interested in how some stories become so powerful, even when upon closer inspection, they seem completely fanciful if not utterly frightening.

![]()

Of late, I’ve been especially interested in the connection between the rise of the field of educational psychology at the turn of the twentieth century and the rise of intelligence testing and teaching machines and now, of course, so-called intelligent machines, AI, that will teach and test. The behaviorist B. F. Skinner – the person perhaps most commonly associated with the phrase “teaching machines.” He is, I would argue, one of the most influential figures on education technology, taking the insights he’d gleaned from working with animals to devise a theory – and machines – to shape and reward student behavior. Other, earlier contributors to the field – Edward Thorndike, Lewis Terman, Robert Yerkes, Sidney Pressey. The former three gave us experimental educational psychology, the multiple choice test, intelligence testing. The latter designed what’s often recognized as the first teaching machine.

These three areas – educational psychology, intelligence testing, and teaching machines – work together in ways that I don’t think we often acknowledge, particularly when we argue ed-tech is an agent of liberation and not an agent of surveillance, a tool that supports curiosity and not one whose earliest designs involved standardization and control.

The title of this talk is “The Golden Lasso of Education Technology,” and I mean this as a nod to the ways in which education technology has bound us – our stories, our budgets, our practices, our imaginations – in the shiniest of restraints.

![]()

It is, of course, also a nod to Wonder Woman.

Wonder Woman first appeared in All Star Comics #8 in December 1941 and was featured on her first cover in Sensation Comics #1 in January 1942.

![]()

She’s been in print now for over 70 years and is considered the third of DC Comics’ “big three,” along with Superman and Batman. That being said, she’s never been one of the bestsellers, ranking according to some recent reports sixth in sales at DC – after Batman, Superman, Green Lantern, the Flash, and Aquaman. (Ouch.)

![]()

Wonder Woman has always been synonymous with women’s liberation, well before she was featured on the cover of the first issue of Ms. magazine in 1972. The Amazonian princess Diana came to the United States, like so many superheroes, to save the country during World War II (and she’s been here fighting ever since for truth and justice – which include, no doubt, women’s rights).

![]()

The persona Diana adopted when she left her home island, Wonder Woman, has superhuman strength and magico-technological devices, although these are both categorically different than her peers Batman and Superman.

![]()

She has her roots in Greek mythology, as her debut declared: “As lovely as Aphrodite – as wise as Athena – with the speed of Mercury and the strength of Hercules – she is known only as Wonder Woman, but who she is, or whence she came, nobody knows!”

![]()

Wonder Woman has magical bracelets that can deflect weapon fire – they also rein in her strength interestingly, and they underscore a weakness that runs through the comic’s earliest issues. Stripped of the bracelets in Sensation Comics #19, Wonder Woman becomes wild, violent. “The bracelets bound my strength to good purposes – now I’m completely uncontrolled!” she says. “I’m free to destroy like a man!”

![]()

Wonder Woman also carries her golden lasso. Whoever is caught in the rope – and Wonder Woman wields it with great accuracy – is compelled to speak the truth.

This is often the point where, in Wonder Woman lore, people gesture to her creator William Moulton Marston (working under the pen-name Charles Marston), who also invented an early lie detector machine.

![]()

The lasso of truth is Wonder Woman’s lie detector machine, some argue – one undeterred by legalities like the so-called “Frye standard” from 1923 that decreed what might count as admissible “scientific evidence.” This standard was based on a court case in which Marston’s testimony as an “expert witness” was called into question.According to the Supreme Court at the time, lie detector tests were inadmissible.

This tension between “what counts” as science is something that underscores education and education technology as well. Is teaching an art? Or is it a science? Is psychology, education psychology a science? Or is it simply philosophy with more experiments and a dash of statistics? Machines – teaching machines, lie detector machines – signify science. But really, what do we know for sure about knowing, about learning as scientific processes? And how, of course, is that, along with the demands on teaching, increasingly shaped by what machines can measure?

![]()

Wonder Woman’s creator William Moulton Marston was a fascinating character in his own right – he lived under one roof with two women, including the niece of birth control advocate Margaret Sanger, and he had children by both of them, as Jill Lepore has methodically chronicled in her recent book The Secret History of Wonder Woman. His wife Elizabeth Holloway Marston boasted as many academic credentials as her husband, and she supported the family throughout his experiments with academia, Hollywood, and publishing. Olive Byrne also supported the family, taking care of the children and writing articles in Family Circle (also under a pen-name), some of which involved interviews with Marston and arguments as to why mothers should let their children read comics (the equivalent perhaps of today’s arguments as to why mothers should let their children play video games). Both Holloway Marston and Byrne contributed to Wonder Woman’s stories and her iconography and clearly to Marston’s philosophy about love and power.

Wonder Woman is sometimes read as an utopian tale, where women are not just sexually liberated, but morally superior.

![]()

Wonder Woman comes from the island of the Amazons in order to save man (lower-case and capital-M man). But her form of female domination, as envisioned by Marston at least, is intertwined with submission. And in the earliest comics, it’s hard to find an issue – hell, a page – without bondage.

![]()

As Lepore writes,

In episode after episode, Wonder Woman is chained, bound, gagged, lassoed, tied, fettered, and manacled. She’s locked in an electric cage. She’s winched into a straitjacket, from head to toe. Her eyes and mouth are taped shut. She’s roped and then coffined in a glass box and dropped into the ocean. She’s locked in a bank vault. She’s tied to railroad tracks. She’s pinned to a wall. Once, so that she can be both entirely bound and movable, her fettered feet are welded to roller skates. “Great girdle of Aphrodite!” she cries. “Am I tired of being tied up!”

![]()

As Marston wrote to a member of the DC editorial advisory board, attempting to explain why Wonder Woman was morally acceptable fare,

This, my dear friend, is the one truly great contribution of my Wonder Woman strip to moral education of the young. The only hope for peace is to teach people who are full of pep and unbound force to enjoy being bound – enjoy submission to kind authority, wise authority, not merely tolerate such submission. Wars will only cease when humans enjoy being bound.

I hear echoes of that argument in much of education technology today, a subtext of domination and submission. There is freedom in scripted adaptive learning, for example. I invoke Wonder Woman here as a beloved figure, but one that always makes us uncomfortable. And I want to sketch out further connections for us to sit with – uncomfortably – with ed-tech’s “golden lasso.” I want us to think about the history of machines and the mind. I want us to think about the stories we tell about truth and justice and power. After all, Marston’s lie detector machine shares a history with education psychology and by extension education technology.

Marston’s work remained on the margins of his field, to be clear. Despite a promising career as an undergraduate at Harvard, he was largely rejected by academia (for a number of reasons that have nothing to do with Wonder Woman). He took his theories and his experiments elsewhere: to Hollywood, and eventually to comics.

For many years Marston was an adjunct professor. He could not secure permanent employment at the universities he worked at, including Harvard, Ratcliffe, Tufts, Columbia, and American University. (Ironically, I suppose, Marston was arrested and charged with fraud while chair of the psychology department at the latter.) Despite not remaining in academia, Marston was present at these elite universities as the disciplines of educational psychology and experimental psychology were being developed. He was a student of Hugo Münsterberg, who William James had recruited in 1892 to come to Harvard and run its brand new psychology lab.

![]()

Münsterberg frequently experimented on the young women who took classes at the Harvard annex (the annex became Radcliffe in 1894). Although he was still an undergraduate, Marston was hired by Münsterberg to help him teach at Radcliffe, in the words of Jill Lepore, “strapping girls to machines.”

![]()

It was at Harvard/Ratcliffe where Marston assisted Münsterberg with his experiments that sought to identify deception, based on the subject’s physical response – that is, they wanted to devise a methodology, a machine that could distinguish the truth from a lie. Marston’s research specifically involved measuring systolic blood pressure.

![]()

Marston was also interested in the nascent film industry and was curious “what psychological factors are involved when we watch happenings on the screen?” (He was interested too in marketing these insights to screenwriters and studios.) He conducted experiments with nickelodeons, also involving “strapping girls to machines” – always the self-promoter, he called this machine “the Love Meter” – in order to monitor them while they watched movies. In one experiment, he gauged the reactions of showgirls to the silent film Flesh and the Devil starring Greta Garbo. Marston claimed that this study proved that brunettes were more easily aroused than blondes. Blondes react to more “superficial things.”

![]()

I want to pause here (again) and think of the reverberations of this sort of experimentation that are still felt today – the “strapping girls (and boys) to machines” that still happens in education technology in the name of “science.” Take, for example, the galvanic skin response bracelets that the Gates Foundation funded in order to determine “student engagement.” The bracelets purport to measure “emotional arousal,” and as such, researchers wanted to use measurements from the bracelets to help teachers devise better lessons. This is arguably not that different from Marston’s work in Hollywood. It’s particularly not that different if you see education, much like film, in the business of “content delivery.” Make a better lesson, make a better movie.

![]()

The strapping of viewers to machines doesn’t have to look like blood pressure cuffs or galvanic skin response bracelets. I’d argue that much of education technology involves a metaphorical “strapping of students to machines.” Students are still very much the objects of education technology, not subjects of their own learning. Today we monitor not only students’ answers – right or wrong – but their mouse clicks, their typing speed, their gaze on the screen, their pauses and rewinds in videos, where they go, what they do, what they say. We do this because, like early psychologists, we still see these behaviors as indicative of “learning.” (And deception too, I suppose.) Yes, despite psychology’s move away from behaviorism over the course of the twentieth century – its “cognitive turn” if you will – education technology, as with computer technology writ large, remains a behaviorist endeavor.

Now Marston wasn’t a radical behaviorist like B. F. Skinner, who famously rejected the notion that people had an “inner mind” at all. Marston was incredibly interested in emotions, publishing Emotions of Normal People in 1928. But Marston did believe that emotions were expressed in behaviors – as such, they could be monitored and altered. (For what it’s worth, Marston’s theories from that book led to the development of DISC assessment, which is often used by HR departments as a personality test of sorts – a self-help intervention, if you will, to see how you interact with others in the office.)

It is in a similar sort of work-based assessment where education technology can find another one of its roots – namely in the recruitment, testing, and training of soldiers. Like many psychologists of his day, Marston saw World War I as an opportunity to further his research. (At the time, he was still in academia, not in comics.)

![]()

On April 6, 1917, the day that Congress declared war, a group of psychologists gathered at Harvard, including Herbert Langfeld, Marston’s undergraduate advisor, and Robert Yerkes, then the president of the American Psychological Association. They formed the Psychology Committee of the National Research Council. Its task: “the psychological examining of recruits to eliminate the mentally unfit.”

While Marston’s work involved testing deception via machine – something with obvious wartime applicability – most of the wartime efforts of psychologists concerned assessing recruits’ intelligence – some 1.75 million men were tested – a project that was deeply intertwined with eugenics and the belief that intelligence was determined by biology and that socio-economic differences among people and groups of people are inherited. Yerkes, for example once said that “no one of us as a citizen can afford to ignore the menace of race deterioration.” As evolutionary biology Stephen Jay Gould chronicles in his book The Mismeasure of Man, Yerkes worked with Lewis Terman, a Stanford professor responsible for localizing Alfred Binet’s intelligence test to the US (hence, the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales) to create the battery of tests that military recruits would take. Literate recruits would take a written exam, the Army Alpha. Those who failed would be given a pictorial exam, the Army Beta. And those who failed that test would be tested by an individual. Recruits would be ranked, based on their results – A through E – and job placement recommendations would be made based upon these.

![]()

Gould suggests that the Army was quite uninterested in either the psychologists’ input or in their findings. It had its own methodology of promotion, thank you very much. Rather, Gould argues, the major impact of the intelligence testing in World War I was in the trove of data that was gathered by researchers, along with the “general propaganda” – those are Gould’s words – that accompanied Yerkes’ report on what he’d discovered.

The “facts” about intelligence, Gould argues, “continued to influence social policy in America long after their source in the tests had been forgotten.” These “facts” included:

- the average mental age of the white American male was “just above the edge of moronity at a shocking and meager thirteen.” Lewis Terman had previous found that the average age was 16, so “clearly” America was in decline. (Unlike today’s narratives, this was not so much the fault of a “broken education system” as it was the result of immigration and miscegenation.)

- Many European immigrants were found to be morons. “The darker peoples of southern Europe and the Slavs of eastern Europe are less intelligent than the fair peoples of western and northern Europe,” Yerkes found.

- Ranked at the bottom for intelligence were Blacks, actually divided into three groups by the psychologists based on how dark their skin was. Lighter skinned Blacks were found to be more intelligent.

“Science.” These differences were hereditary, Yerkes and others argued – they were not the result of, say, not speaking English or not being literate when given a written exam in English. They certainly were not the result of flaws in the tests the psychologists had designed. Oh no.

And yet, intelligence testing is one of the legacies of World War I. The war was the catalyst for assessment - and for education technology - as we know it today, as the school system in the US opted to replicate elements of this testing process. For much like the military, it wanted to be able to test “at scale,” an incredibly important feature at a time when enrollment in public education in the US was expanding rapidly.

![]()

This is when the multiple choice test came into vogue, thanks in part to the work of Columbia University psychology professor Edward Thorndike – a behaviorist and I should add, a eugenicist. The multiple choice test purports to be more "objective." It takes the power of judgment out of the hands of individual (likely female) teachers. Multiple choice enables standardization.

Moreover, multiple choice assessment promised an education system that could be more efficient. And in conjunction with twentieth century techno-futurism, it was nod towards an education system that could become more automated.

How do you test millions of people? By machine, of course.

![]()

Here’s what psychologist Sidney Pressey wrote in 1926 when he published an article on the device he’d built to do just that:

For a number of years the writer has had it in mind that a simple machine for automatic testing of intelligence or information was entirely within the realm of possibility. The modern objective test, with its definite systemization of procedure and objectivity of scoring, naturally suggests such a development. Further, even with the modern objective test the burden of scoring (with the present very extensive use of such tests) is nevertheless great enough to make insistent the need for labor-saving devices in such work.

A professor at Ohio State University, Sidney Pressey first displayed the prototype of his “automatic intelligence testing machine” at the 1924 American Psychological Association meeting. (He’d come up with the idea before World War I but had to pause his research.) Two years later, he submitted a patent for the device and spent the next decade or so trying to market it to manufacturers and investors, as well as to schools.

It wasn’t his first commercial effort. In 1922 he and his wife Luella Cole published Introduction to the Use of Standard Tests, a “practical” and “non-technical” guide meant “as an introductory handbook in the use of tests” aimed to meet the needs of “the busy teacher, principal or superintendent.” By the mid–1920s, the two had over a dozen different proprietary standardized tests on the market, selling a couple of hundred thousand copies a year, along with some two million test blanks.

As standardized testing had become more commonplace in the classroom by the 1920s, it was already placing a significant burden upon those teachers and clerks tasked with scoring them. Hoping to capitalize yet again on the test-taking industry, Pressey argued that automation could “free the teacher from much of the present-day drudgery of paper-grading drill, and information-fixing - should free her for real teaching of the inspirational.” Again, we hear echoes of that argument today in why teachers should use automated essay grading software and the like.

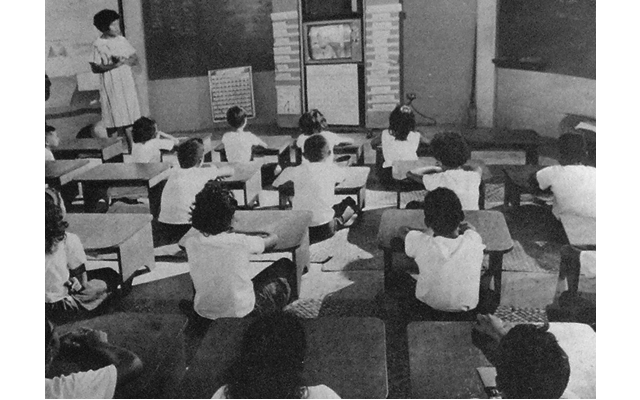

This video from 1964 shows Pressey demonstrating his “teaching machine,” marketed as the Automatic Teacher.

Pressey started looking for investors for his machines in late 1925 – “first among publishers and manufacturers of typewriters, adding machines, and mimeograph machines, and later, in the spring of 1926, extending his search to scientific instrument makers” – but no one was interested. In 1929, he finally signed a contract with the W. M. Welch Manufacturing Company, a Chicago-based company that produced scientific instruments. But as UBC professor Stephen Petrina writes, there were still problems: Pressey wanted to sell the devices for $5 a machine. The manufacturer wanted to charge $50, and said that it “preferred to send out circulars advertising the Automatic Teacher, solicit orders, and then proceed with production if a demand materialized.”

![]()

The demand for teaching machines never did, not until after World War II when Americans became more enthralled with technological gadgets and labor-saving devices – at home, at work, and at school. This was when and how Skinner’s teaching machines became more successful (somewhat more, at least) commercially.

But Pressey’s influence shouldn’t be overlooked simply because he could not commercialize his teaching machine. We can see in Pressey and other early educational psychologists arguments for mechanization that are echoed today.

In his article “Toward the Coming 'Industrial Revolution' in Education” (published in 1932), Pressey wrote that

Education is the one major activity in this country which is still in a crude handicraft stage. But the economic depression may here work beneficially, in that it may force the consideration of efficiency and the need for laborsaving devices in education. Education is a large-scale industry; it should use quantity production methods. This does not mean, in any unfortunate sense, the mechanization of education. It does mean freeing the teacher from the drudgeries of her work so that she may do more real teaching, giving the pupil more adequate guidance in his learning. There may well be an ‘industrial revolution’ in education. The ultimate results should be highly beneficial. Perhaps only by such means can universal education be made effective.

Pressey intended for his automated teaching and testing machines to individualize education. It’s an argument that’s made about teaching machines today too. All of this is – viva la ed-tech revolution. These devices will allow students to move at their own pace through the curriculum. They will free up teachers’ time to work more closely with individual students.

![]()

As Stephen Pretina argues, “the effect of automation was control and standardization.”

The Automatic Teacher was a technology of normalization, but it was at the same time a product of liberality. The Automatic Teacher provided for self-instruction and self-regulated, therapeutic treatment. It was designed to provide the right kind and amount of treatment for individual, scholastic deficiencies; thus, it was individualizing. Pressey articulated this liberal rationale during the 1920s and 1930s, and again in the 1950s and 1960s. Although intended as an act of freedom, the self-instruction provided by an Automatic Teacher also habituated learners to the authoritative norms underwriting self-regulation and self-governance. They not only learned to think in and about school subjects (arithmetic, geography, history), but also how to discipline themselves within this imposed structure. They were regulated not only through the knowledge and power embedded in the school subjects but also through the self-governance of their moral conduct.

![]()

This gets at the heart of the bind that education technology finds itself in – its golden lasso. Education technology promises personalization and liberation, but it’s really, most often in the guise of obedience, a submission to the behavioral expectations and power structures that are part of our educational institutions (and more broadly, of society). It’s a loving authority, I imagine William Moulton Marston might reassure us – stereotypically at least, since the classroom has become a realm (supposedly) ruled by women.

Much like Wonder Woman, education technology claims – wants, even – to be a progressive force for social transformation. But like Wonder Woman, education technology is entangled in conservative, if not reactionary, forces.

Much like Wonder Woman, education technology is, in Marston’s words, “psychological propaganda.” It promises the future, while running students through the paces of a curriculum still largely circumscribed by the past.

![]()

Much like Wonder Woman, education technology insists it offers a scientific intervention. As Philip Sandifer writes in his “critical history” of Wonder Woman, “This is crucial to understanding the nature of Wonder Woman. She's not just a popular response to Marston’s psychological theories, nor is she just the product of his fetishes. Rather, she’s part of a concentrated effort to advance a technocratic worldview that comes not from the hard sciences but from the field of psychology at a point when it was caught between two competing approaches.” In post-War America, that really cannot be understated. We have these early twentieth century efforts – intelligence testing, Pressey’s Automatic Teacher – but it’s in the push and the hope for science and technology after the Second World War that we really see ed-tech take off. Education technology helps to make teaching and learning look like science. It helps to make them look modern, shiny.

Much like Wonder Woman, education technology could serve to extend human capabilities. Instead, it winds up being assigned the role of secretary of the League of Justice, doing menial tasks and not saving the world.

![]()

Much like Wonder Woman, education technology perpetually rejects and re-inscribes its origins, trapped in a cycle of re-starts and re-boots, old narratives redrawn by new artists and engineers, old narratives completely rewritten.

And much like Wonder Woman, that means there is this multiplicity to the whole project. There is not one single, authoritative direction that this story has to go, despite the origin myth originally set for us in the early twentieth century. That’s something quite powerful and subversive. And I think that’s how we can retain hope for a progressive change. But that does mean we have to demand much better stories and not simply fall into a genre that placates us with classic superheroes or that insists that students are ours to rescue.

Image credits: Push-Button Education, Skinner, Thorndike, Terman, Yerkes, Sensation Comics No. 1, Sensation Comics No. 58, Ms. Magazine No. 1, Action Comics No. 1, Sensation Comics No. 51, Sensation Comics No. 3, Sensation Comics No. 6, The Secret History of Wonder Woman, Wonder Woman No. 5, Sensation Comics No. 31, "Why 100,000 Americans Read Comics," Harvard University Archives, Tufts University Digital Collections, Sensation Comics No. 3, Wonder Woman No. 2, Wonder Woman No. 230, The Mismeasure of Man, Wonder Woman No. 46, Sensation Comics No. 7, Sensation Comics No. 36, Superman vs. Wonder Woman, Sensation Comics No. 102, Wonder Woman No. 88