The Rise of Programmed Instruction

In the 1948 utopian novel Walden Two, a small group - a couple of academics, two of their former students and their girlfriends - visit an intentional community established by a former colleague, T. E. Frazier. The novel’s narrator, Professor Burris, a university psychology professor, relates the details of their tour, given by the enthusiastic Frazier.

Frazier explains to the group the workings of the community, called Walden Two as a nod to the self-sufficiency and simplicity promoted by Henry David Thoreau. But while Thoreau lived alone at Walden Pond, Walden Two boasts almost a thousand residents. The novel itself is a lengthy explanation of the ideas and practices that drive the community: how its economy, governance, food production, housing, and education function.

Walden Two is an experiment, a community-wide experiment in “behavioral engineering.” Frazier notes the number of benefits that come from this - that the members only work four hours a day, for example; and he reiterates how happy everyone is - in part, no doubt, because this engineering begins at birth and the reinforcement occurs in every activity.

One of the visitors, Professor Castle, a professor of ethics and philosophy, remains incredibly skeptical, grilling Frazier throughout the tour. Castle is particularly concerned that the community at Walden Two is profoundly anti-democratic. “The people have no voice,” Professor Castle observes. “The people have all the voice they have any need for,” Frazier responds, later arguing that “Democracy is the spawn of despotism.”

“Now that we know how positive reinforcement works and why negative doesn’t,” [Frazier] said at last, "we can be more deliberate, and hence more successful, in our cultural design. We can achieve a sort of control under which the controlled, though they are following a code much more scrupulously than was ever the case under the old system, nevertheless feel free. They are doing what they want to do, not what they are forced to do. That's the source of the tremendous power of positive reinforcement - there's no restraint and no revolt. By a careful cultural design, we control not the final behavior, but the inclination to behave - the motives, the desires, the wishes.

The curious thing is that in that case the question of freedom never arises."

Walden Two is by no means a great novel. It's not even a good novel. In fact it would hardly be remarkable or memorable at all - except that its author was Harvard psychology professor B. F. Skinner, and the novel is his fictionalized exploration of some of his theories.

Walden Two is by no means a great novel. It's not even a good novel. In fact it would hardly be remarkable or memorable at all - except that its author was Harvard psychology professor B. F. Skinner, and the novel is his fictionalized exploration of some of his theories.

Skinner had developed what he called a theory of “radical behavioralism,” that all human activity can be seen as a behavior and that all behaviors can be modified through reinforcement techniques.

B. F. Skinner is also often credited as the inventor of the teaching machine.

In the preface to an updated version (1976) of Walden Two, Skinner writes,

We know how to solve many educational problems with programmed instruction and good contingency management, saving resources and the time and effort of teachers and students. Small communities are ideal settings for new kinds of instruction, free from interference by administrators, politicians, and organizations of teachers. In spite of our lip service to freedom, we do very little to further the development of the individual.

According to Skinner, teaching machines and behavioral engineering are how the individual should be developed.

Skinner’s Teaching Machines

In his autobiography, B. F. Skinner describes how he came upon the idea of a teaching machine in 1953: Visiting his daughter’s fourth grade classroom, he was struck by the inefficiencies. Not only were all the students expected to move through their lessons at the same pace, but when it came to assignments and quizzes, they did not receive feedback until the teacher had graded the materials - sometimes a delay of days. Skinner believed that both of these flaws in school could be addressed by a machine, so he built a prototype that he demonstrated at a conference the following year, resulting in a brief write-up in the Science News Letter.

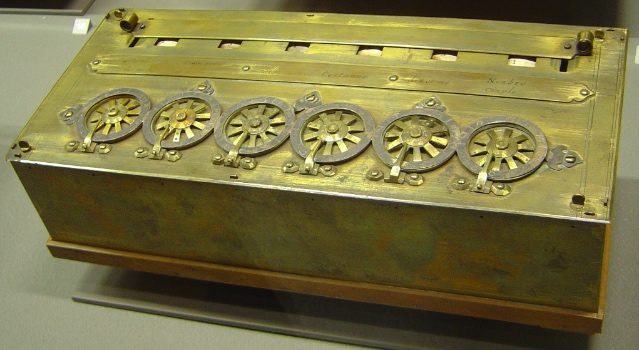

Ohio State University psychology professor Sidney Pressey, who’d patented his design for a teaching machine almost 30 years earlier, read that article and wrote to Skinner; according to Skinner the two had an “exciting discussion” about teaching machines. Although the popular press lauded Skinner as the inventor of the teaching machine, he did give a nod to Pressey for his contributions.

But Skinner made it clear that he had several disagreements with Pressey on his machine’s design. Skinner argued that Pressey had developed a machine for testing, rather than teaching, in part because they were not specifically designed to present students with new material. In order to use Pressey's machines, Skinner argued, students had to already have external exposure to the information. Skinner believed that his machines, by introducing new concepts in incremental steps, actually "taught."

This incrementalism was important for Skinner because he believed that the machines could be used to minimize the number of errors that students made along the way, maximizing the positive reinforcement that students received. Materials needed to be broken down into small chunks and organized in a logical fashion for students to move through. Skinner called this process “programmed instruction.”

In acquiring complex behavior the student must pass through a carefully designed sequence of steps, often of considerable length. Each step must be so small that it can always be taken, yet in taking it the student moves somewhat closer to fully competent behavior. The machine must make sure that these steps are taken in a carefully prescribed order.

Skinner’s machines also differed from Pressey's because while the latter relied on multiple choice options, Skinner’s machine had students compose the response:

Sets of separate presentations or ‘frames’ of visual material are stored on disks, cards, or tapes. One frame is presented at a time, adjacent frames, being out of sight. In one type of machine the student composes a response by moving printed figures or letters. His setting is compared by the machine with a coded response. If the two correspond, the machine automatically presents the next frame. If they do not, the response is cleared, and another must be composed. The student cannot proceed to a second step until the first has been taken.

In more advanced versions of the machine (designed for older students), students write their answers by hand and then pull a level to expose the correct answer:

If the two responses correspond, he moves the lever horizontally. This movement punches a hole in the paper opposite his response, recording the fact that he called it correct, and alters the machine so that the frame will not appear again when the student works around the disk a second time.

Whether the response was correct or not, a second frame appears when the lever is returned to its starting position. The student proceeds in this way until he has responded to all frames. He then works around the disk a second time, but only those frames appear to which he has not correctly responded. When the disk revolves without stopping, the assignment is finished. (The student is asked to repeat each frame until a correct response is made to allow for the fact that, in telling him that a response is wrong, such a machine tells him what is right.)

Again, wanting to minimize students getting answers wrong, Skinner frowned upon multiple choice. He also wanted the student to be able to construct the response, not simply choose a response from a pre-set list.

Skinner had a dozen of the machines installed in the self-study room at Harvard in 1958 used to teach the undergraduate course Natural Sciences 114. “Most students feel that machine study has compensating advantages. They work for an hour with little effort, and they report that they learn more in less time and with less effort than in conventional ways.” And if it’s good enough for Harvard students…

“Machines such as those we use at Harvard,” Skinner boasted, “could be programmed to teach, in whole and in part, all the subjects taught in elementary and high school and many taught in college.”

Education Technology as Operant Conditioning

“Behaviorism,” Skinner wrote, “is not the science of human behavior; it is the philosophy of that science.” Behaviorism offered a challenge to the (fairly new at the time) field of psychology that was focused primarily on the “inner workings” of the human mind - feelings, the subconscious, cognition. As a result some other behaviorists had focused instead on public displays of activity, arguing that “mental life” could not be really examined.

Addressing any sort of social problem, for Skinner, meant addressing behaviors. As he wrote in Beyond Freedom and Dignity, “We need to make vast changes in human behavior.... What we need is a technology of behavior.” Teaching machines are one such technology.

By arranging appropriate “contingencies of reinforcement,” specific forms of behavior can be set up and brought under the control of specific classes of stimuli. The resulting behavior can be maintained in strength for long periods of time. A technology based on this work has already been put to use in neurology, pharmacology, nutrition, psychophysics, psychiatry, and elsewhere.

The analysis is also relevant to education. A student is “taught” in the sense that he is induced to engage in new forms of behavior and in specific form upon specific occasions. It is not merely a matter of teaching him what to do; we are as much concerned with the probability that appropriate behavior will, indeed, appear at the proper time - an issue which would be classed traditionally under motivation.

Teaching - with or without machines - was viewed by Skinner as reliant on a “contingency of reinforcement.” The problems with human teachers’ reinforcement were severalfold. First, the reinforcement did not occur immediately; that is, as Skinner observed in his daughter’s classroom, there was a delay between students completing assignments and quizzes and their work being corrected and returned. Second, much of the focus on behavior (as it is traditionally defined at least) in the classroom involves punishing students for bad behavior rather than rewarding them for good.

Any one who visits the lower trades of the average school today will observe that a change has been made, not from aversive to positive control, but from one form of aversive stimulation to another.

But with the application of behaviorism and the development of teaching machines, “There is no reason,” insisted Skinner, “why the schoolroom should be any less mechanized than, for example, the kitchen.”

The Sputnik Moment and the Skinner’s Box

Skinner’s insistence on a classroom as mechanized as a kitchen fit perfectly with the post-war obsession in America for home appliances, gadgets, and automation.

Sidney Pressey had struggled to find a manufacturer or a market for his “Automatic Teacher” in the 1920s. But now America was facing a “Sputnik” moment; more science and technology were necessary to address the apparent failures of the US education system. In September 1958, Congress passed the National Defense Education Act, that in part provided funding to improve the teaching of science and mathematics. Money was available – from Washington and from philanthropic organizations like the Ford Foundation – for experiments in education. Among these: programmed instruction and teaching machines.

Sidney Pressey had struggled to find a manufacturer or a market for his “Automatic Teacher” in the 1920s. But now America was facing a “Sputnik” moment; more science and technology were necessary to address the apparent failures of the US education system. In September 1958, Congress passed the National Defense Education Act, that in part provided funding to improve the teaching of science and mathematics. Money was available – from Washington and from philanthropic organizations like the Ford Foundation – for experiments in education. Among these: programmed instruction and teaching machines.

As Ludy Benjamin notes in his “History of Teaching Machines,”

The boom in teaching machines was underway in the early 1960s, and most of the devices were based on Skinner’s theory of learning. One of the most popular machines was the Min-Max, marketed by Grolier, Inc. The company initially sold the Min-Max door to door, using its force of 5,000 encyclopedia salespeople. The machine, which was designed by Teaching Machines, Inc., a company headed by psychologist Lloyd Homme, was one of the cheapest on the market at $20, and within two years Grolier had sold 100,000 of them. The company sales representatives used Skinner’s and Harvard University’s name in its marketing despite requests from Skinner that they stop.

For his part, Skinner worked with IBM to develop (and patent) a teaching machine.

From Popular Science in 1962: Norman “Crowder estimates that by 1965, half of all students will be using teaching machines, at least for a course or two.”

These sorts of predictions echo those we continue to see in the media about the promises of an “ed-tech revolution.” Indeed that’s where the story of teaching machines really took off: in the popular press.

The problem that teaching machines quickly ran into – in addition to the problem that Pressey had faced, of course: schools’ inability to actually afford the devices – was that these headlines often tied the teaching machine to some of Skinner’s other work, particularly with animal experiments. Skinner himself had argued that his theories and methodologies offered the same insight into animal behavior as they did student behavior:

Comparable results have been obtained with pigeons, rats, dogs, monkeys, human children, and psychotic subjects. In spite of great phylogenic differences, all these organisms show amazingly similar properties of the learning process. It should be emphasized that this has been achieved by analyzing the effects of reinforcement and by designing techniques which manipulate reinforcement with considerable precision. Only in this way can the behavior of the individual organism be brought under such precise control.

And so the headlines echoed this: “Can People Be Taught Like Pigeons?”

Some articles linked the teaching machines to another invention that Skinner had made for his daughter: “the Air Crib,” a climate controlled environment for a baby. The Ladies Home Journal ran a story on the crib in 1945 titled “Baby in a Box,” again a reference to the “Skinner Box,” the operant conditioning chamber that Skinner had designed for his experiments on rats and pigeons. The image that accompanied the article furthered the connection: Skinner’s daughter in the crib with her face and hands pressed against the glass. There were a number of rumors about her, as Deborah Skinner Buzan herself wrote about in an op-ed “I Was Not a Lab Rat” in The Guardian:

I had gone crazy, sued my father, committed suicide. My father would come home from lecture tours to report that three people had asked him how his poor daughter was getting on. I remember family friends returning from Europe to relate that somebody they had met there had told them I had died the year before. The tale, I later learned, did the rounds of psychology classes across America. One shy schoolmate told me years later that she had shocked her college psychology professor, who was retelling the rumour about me, by banging her fist on her desk, standing up and shouting, “She’s not crazy!”

But the negative associations with this sort of controlled conditioning of children persisted.

Headlines also tapped into fears about the sorts of "cultural engineering" - a phrase that Skinner uses in Walden Two - that these devices might enable: “Will Robots Teach Your Children?”; “Which Is It? New World of Teaching Machines or Brave New Teaching Machines?” One magazine warned of the totalitarian implications of the devices — what would happen if Hitler or Stalin had teaching machines?

With teaching machines, what happens to intellectual freedom? What happens to student's agency?

Beyond Freedom and Dignity and Back Again

In 1971, Skinner published his book Beyond Freedom and Dignity, a book that argues in effect, that concerns about – even desires for – “free will” are entirely misplaced.

What we may call the “literature of freedom” has been designed to induce people to escape from or attack those who act to control them aversively. The content of the literature is the philosophy of freedom, but philosophies are among those inner causes which need to be scrutinized… . The literature of freedom, on the other hand, has a simple objective status. It consists of books, pamphlets, manifestoes, speeches, and other verbal products, designed to induce people to act to free themselves from various kinds of intentional control. It does not impart a philosophy of freedom; it induces people to act.

Skinner’s book received a devastating review by MIT professor Noam Chomsky in The New York Review of Books. As a “defender of freedom” as well as a linguist who believed that language was biologically determined, rather than, as Skinner contended, behavioral, Chomsky argued that Skinner’s assertions about behaviorism and the development of technologies of control were backed by no evidence. Indeed his claims “dissolve into triviality or incoherence under analysis.” But this isn’t simply a critique of behaviorism by Chomsky. As the title of his review makes clear, this is “The Case Against B. F. Skinner.”

…There is nothing in Skinner’s approach that is incompatible with a police state in which rigid laws are enforced by people who are themselves subject to them and the threat of dire punishment hangs over all. Skinner argues that the goal of a behavioral technology is to “design a world in which behavior likely to be punished seldom or never occurs” – a world of “automatic goodness” (p. 66). The “real issue,” he explains, “is the effectiveness of techniques of control” which will “make the world safer.” (pp. 66 and 74).

Although Chomsky condemns Skinner’s work as a failure of scientific theory (“Skinner confuses ‘science’ with terminology”), he is also concerned here with the larger implications politically and socially. What happens to the public when presented with this disdain for freedom and dignity? What happens to the public when presented with technologies that promise a cultural engineering that would remove all manners of strife?

The public, writes Chomsky, “may even choose to be misled into agreeing that concern for freedom and dignity must be abandoned, perhaps out of fear and a sense of insecurity about the consequences of a serious concern for freedom and dignity. The tendencies in our society that lead toward submission to authoritarian rule may prepare individuals for a doctrine that can be interpreted as justifying it.”

With this book review, Chomsky is often credited for helping to discredit Skinner and behaviorism. (Skinner did continue writing, of course, including his three-part autobiography.) Much like the teaching machines themselves, Skinner and his theories fell out of favor.

But that’s not to say that the influence of Skinner and behaviorism are gone. Far from it. Behaviorism has persisted - although often unnamed and un-theorized - in much of the technology industry, as well as in education technology – in Turing machines not simply in teaching machines.

From Bob Johnstone’s book Never Mind the Laptops: Kids, Computers, and the Transformation of Learning:

From Bob Johnstone’s book Never Mind the Laptops: Kids, Computers, and the Transformation of Learning:

The use of Logo and LogoWriter underscores that the approach to one-to-one computing at the Methodist Ladies’ College was constructionist, relying heavily on the work of Seymour Papert. That is, the laptops were not introduced so as to boost the girls’ skills at utilizing business applications; they were not introduced so as to run the students through their paces via computer-assisted instruction; they were not introduced to make traditional education more efficient. The laptops were about supporting the girls’ construction of knowledge by placing in their hands these new, powerful, programmable computing machines. And in the words of MLC principal David Loader, “From the introduction of laptops, monumental consequences flowed. A school, its culture, curriculum, and teaching-learning paradigm began to be transformed.”

The use of Logo and LogoWriter underscores that the approach to one-to-one computing at the Methodist Ladies’ College was constructionist, relying heavily on the work of Seymour Papert. That is, the laptops were not introduced so as to boost the girls’ skills at utilizing business applications; they were not introduced so as to run the students through their paces via computer-assisted instruction; they were not introduced to make traditional education more efficient. The laptops were about supporting the girls’ construction of knowledge by placing in their hands these new, powerful, programmable computing machines. And in the words of MLC principal David Loader, “From the introduction of laptops, monumental consequences flowed. A school, its culture, curriculum, and teaching-learning paradigm began to be transformed.”

In 1982, Jobs approached his Representative, Pete Stark, who drafted a bill was drafted to introduce to Congress.

In 1982, Jobs approached his Representative, Pete Stark, who drafted a bill was drafted to introduce to Congress.

Calculators had already become important business tools, well before the handheld calculator. And in the 1970s, with a fair amount of debate about their effect on learning, calculators slowly began to enter the classroom.

Calculators had already become important business tools, well before the handheld calculator. And in the 1970s, with a fair amount of debate about their effect on learning, calculators slowly began to enter the classroom.

“SRA Reading Laboratory 2.0 is an interactive, personalized reading practice program based on the classic SRA Reading Laboratory print program created by Don H. Parker, PhD. now featuring innovative 21st century digital and social skills.” -- so say the marketing materials for the current version of the SRA software, invoking many of today's most frequently used buzzwords: "21st century,""interactive,""personalized."

“SRA Reading Laboratory 2.0 is an interactive, personalized reading practice program based on the classic SRA Reading Laboratory print program created by Don H. Parker, PhD. now featuring innovative 21st century digital and social skills.” -- so say the marketing materials for the current version of the SRA software, invoking many of today's most frequently used buzzwords: "21st century,""interactive,""personalized."