Part 5 of my Top Ed-Tech Trends of 2012 series

The Year of the MOOC

Massive Open Online Courses. MOOCs. This was, without a doubt, the most important and talked-about trend in education technology this year.

And oh man, did we talk about it. MOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCsMOOCs ad infinitum.

The Year of the MOOC

![]() In retrospect, it’s not surprising that 2012 was dominated by MOOCs as the trend started to really pick up in late 2011 with the huge enrollment in the three computer science courses that Stanford offered for free online during the Fall semester, along with the announcement of MITx in December. Add to that the increasing costs of college tuition and arguments that there’s a “higher education bubble,” and the promise of a free online university education obviously hit a nerve.

In retrospect, it’s not surprising that 2012 was dominated by MOOCs as the trend started to really pick up in late 2011 with the huge enrollment in the three computer science courses that Stanford offered for free online during the Fall semester, along with the announcement of MITx in December. Add to that the increasing costs of college tuition and arguments that there’s a “higher education bubble,” and the promise of a free online university education obviously hit a nerve.

But the obstacles to the adoption of and accreditation for MOOCs by the university establishment were (are) still overwhelming enough that Dave Cormier listed (MIT and) MOOCs as one of his “black swans for education in 2012” when he made his education predictions for the year. (A “black swan” is an unexpected, but game-changing event.)

Who cares what Cormier thinks and predicts? More on that in a minute. But first, a brief timeline of the what the New York Times has called “The Year of the MOOC”:

January:

- Googler and Stanford professor (and professor for the university’s massive AI class) Sebastian Thrun announces he’s leaving Stanford to launch Udacity, his own online learning startup.

February:

- MITx opens for enrollment. Its first class: “6.002x: Circuits and Electronics.”

April:

- Stanford professors Andrew Ng and Daphne Koller (also involved with Stanford’s fall 2011 MOOCs) officially launch their online learning startup Coursera. They also announce that they’ve raised $16 million in funding.

May:

June:

- Udacity announces it’s partnering with Pearson, which will offer onsite testing for its classes.

- Google offers a MOOC on “power searching.”

- The Board of Visitors at the University of Virginia fire president Teresa Sullivan, in part reveal emails, because they see her as slow to jump on the MOOC bandwagon. Following a huge outcry by faculty, students, and alumni, Sullivan is reinstated; UVA joins Coursera the following month (in a deal that was already in the works before Sullivan’s ouster).

July:

- 12 more universities join Coursera (University of Pennsylvania, Princeton, University of Michigan and Stanford are Georgia Tech, Duke University, University of Washington, Caltech, Rice University, University of Edinburgh, University of Toronto, EPFL - Lausanne (Switzerland), Johns Hopkins University (School of Public Health), UCSF, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and the University of Virginia.) This brings the number of universities involved to 16.

August:

- University of California, Berkeley joins edX.

- P2PU, OpenStudy, Codecademy, and MIT Opencourseware team up to offer a “mechanical MOOC” to teach introductory Python.

- MOOC MOOC— a meta-MOOC, if you will — runs for a week.

September:

- 17 more schools join Coursera: Berklee College of Music, Brown University, Columbia University, Emory University, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Ohio State University, University of British Columbia, University of California at Irvine, University of Florida, University of London, University of Maryland, University of Melbourne, University of Pittsburgh, Vanderbilt University, and Wesleyan University. Coursera announces it has also raised an additional $3.7 million in funding.

- Google open sources Course Builder, a platform it had used to run its own “power search” MOOC earlier in the summer. The Saylor Foundation announces it plans to utilize the technology to offer courses.

- George Mason University professors Tyler Cowan and Alex Tabarrok launch MRUniversity, an economics MOOC.

October:

- The University of Texas system joins edX.

- Coursera strikes a deal with Antioch University. The latter will license courses from Coursera and will offer these for credit to its students.

- Udacity announces it has raised $15 million in funding from Andreessen Horowitz.

- The LMS Instructure launches the Canvas Network, a catalog of free, open online classes run on the Canvas LMS by Canvas customers.

November:

- The American Council on Education says it will initiate a credit-equivalency evaluation of several Coursera courses.

- Several Massachusetts community college partner with edX to offer “blended” versions of MIT courses through an effort funded by the Gates Foundation.

December:

The Forgotten History of MOOCs

![]() Back to Cormier, the guy who coined the term “MOOC” back in 2008, long before Stanford’s massively-hyped online artificial intelligence class. That’s an important piece of education technology history that’s been overlooked a lot this year as Sebastian Thrun and his Stanford colleagues have received most of the credit in the mainstream press for “inventing” the MOOC.

Back to Cormier, the guy who coined the term “MOOC” back in 2008, long before Stanford’s massively-hyped online artificial intelligence class. That’s an important piece of education technology history that’s been overlooked a lot this year as Sebastian Thrun and his Stanford colleagues have received most of the credit in the mainstream press for “inventing” the MOOC.

But MOOCs have a longer history, dating back to some of the open online learning experiments conducted by Cormier, George Siemens, Stephen Downes, Alec Couros, David Wiley and others. Downes and Siemens’ 2008 class "Connectivism and Connective Knowledge,”for example, was offered to some 20-odd tuition-paying students at the University of Manitoba, along with over 2300 who signed up for a free and open version online.

In July, Downes made the distinction between “cMOOCs,” the types he has offered, and “xMOOCs,” those offered by Udacity, Coursera, edX and others. The terminology is very useful to help distinguish between the connectivist origins of MOOCs (and the connectivist principles and practices of open learning and online networks) and the MOOCs that have made headlines this year (with their emphasis on lecture videos and multiple choice tests). While cMOOCs are strongly connectivist and Canadian, xMOOCs, as Mike Caulfield contends, exist “at the intersection of Wall Street and Silicon Valley.”

The Technology of xMOOCs

![]() While a lot of the mainstream press’s attention to MOOCs has focused on the content, the class sizes, and the (potential) credentials, the technology that underpins these online courses is incredibly important — and something too that highlights the differences between xMOOCs and cMOOCs.

While a lot of the mainstream press’s attention to MOOCs has focused on the content, the class sizes, and the (potential) credentials, the technology that underpins these online courses is incredibly important — and something too that highlights the differences between xMOOCs and cMOOCs.

The cMOOCs rely on tools like Downes’ gRSShopper, which as he describes it, “is a personal web environment that combines resource aggregation, a personal dataspace, and personal publishing. It allows you to organize your online content any way you want to, to import content – your own or others’ – from remote sites, to remix and repurpose it, and to distribute it as RSS, web pages, JSON data, or RSS feeds.”

Rather than driving users to a course website or a learning platform for all their interactions, the users on gRSShopper “are assumed to be outside the system for the most part,” writes Downes, “inhabiting their own spaces, and not mine.” xMOOCs, on the other hand, look an awful lot like an LMS.

There’s more too under the hood of the xMOOCs when it comes to assessment. With their origins in the Stanford CS department, with an early emphasis on CS classes, and with the scale that many of their enrollments are reaching, it makes sense that many of these course utilize automation to assess students’ quizzes and homework assignments.

But when Coursera launched, it said that it planned to expand the course catalog beyond engineer. From my post in April:

“How will you grade this?!” I asked (fearing, I confess, the machine learning professor Ng’s answer would be “machine learning, of course!”). But Koller and Ng said that they remained skeptical about the ability of that technology to offer high quality feedback or assessment for students. So they’ve built something else – not an automated grading system.

Rather, says Ng, the engineering efforts at the startup have been focused on “building up a peer grading technology” where students are trained to grade each others’ work according to the professor’s specifications. It’s what Ng described as a “calibrated peer-review” – in other words, a little bit peer review and a little bit crowdourcing. The latter works akin to Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, whereby microtasks are distributed and labeled and as a result “the best” feedback can be surfaced. “The numerical grade, while useful,” says Ng, “isn’t really the best form of feedback.” Students need feedback, not just grades.

Will the students in the Coursera classes will be supportive of one another (it’s a question I raise based in part on my experiences in the Udacity forums)? That remains to be seen. Nonetheless, the focus on peer feedback is an interesting one, as talk about “scaling education” tends to focus on boosting the technology capacity and not boosting human connectivity.

As it turns out, the peer assessment — at least in its earliest applications — didn’t work out so well.

University of Oklahoma professor Laura Gibbs chronicled many of the problems in the Coursera Fantasy and Science Fiction class on her blog: students were unprepared to give feedback to one another; there were language barriers; there was no opportunity to give feedback on the feedback; the anonymity of the feedback process caused lots of problems and often highlighted the lack of community (and responsibility to it) in these massive classes.

Issues with the peer assessment process prompted some instructors to drop it as part of their course requirements.

The Pedagogy of MOOCs

The differences between xMOOCs and xMOOCs are also evident in their respective pedagogies. In June, George Siemens outlined the “theories that underpin our MOOCs,” highlighting some of these differences. He writes,

The Coursera/EDx MOOCs adopt a traditional view of knowledge and learning. Instead of distributed knowledge networks, their MOOCs are based on a hub and spoke model: the faculty/knowledge at the centre and the learners are replicators or duplicators of knowledge. That statement is a bit unfair (if you took the course with Scott E. Page at Coursera, you’ll recognize that the content is not always about duplication). Nor do our MOOCs rely only on generative knowledge. In all of the MOOCs I’ve run, readings and resources have been used that reflect the current understanding of experts in the field. We ask learners, however, to go beyond the declarations of knowledge and to reflect on how different contexts impact the structure (even relevance) of that knowledge. Broadly, however, generative vs. declarative knowledge captures the epistemological distinctions between our MOOCs and the Coursera/EDx MOOCs. Learners need to create and share stuff – blogs, articles, images, videos, artifacts, etc.

As I note in an earlier post about the Flipped Classroom, much of what’s being lauded as “revolutionary” and as “disrupting” traditional teaching practices here simply involves videotaping lectures and putting them online. While xMOOCs might be changing education by scaling this online delivery, we need to ask, “Are they really changing how people teach?”

The Students

MOOCs are, however, changing how people learn, if for no other reason than they are offering lectures, quizzes, educational resources, and possibly even credentialling to anyone with Internet access.

So who are these students? Demographics data about MOOC enrollment is hard to find, but in June, Inside Higher Ed published some about Andrew Ng’s Stanford Machine Learning class:

Among 14,045 students in the Machine Learning course who responded to a demographic survey, half were professionals who currently held jobs in the tech industry. The largest chunk, 41 percent, said they were professionals currently working in the software industry; another 9 percent said they were professionals working in non-software areas of the computing and information technology industries.

Many were enrolled in some kind of traditional postsecondary education. Nearly 20 percent were graduate students, and another 11.6 percent were undergraduates. The remaining registrants were either unemployed (3.5 percent), employed somewhere other than the tech industry (2.5 percent), enrolled in a K–12 school (1 percent), or “other” (11.5 percent).

A subset (11,686 registrants) also answered a question about why they chose to take the course. The most common response, given by 39 percent of the respondents, was that they were “just curious about the topic.” Another 30.5 percent said they wanted to “sharpen the skills” they use in their current job. The smallest proportion, 18 percent, said they wanted to “position [themselves] for a better job.”

And the majority of the students — in that class at least — hail from outside the U.S., with India, Brazil, Russia, and Britain being the most prevalent nationalities.

It was students — two from India and one from Canada — who created what I think is the among most important MOOC innovations this year — 6.003z. As I wrote in August, “6.003z is the creation of Amol Bhave, a 17-year-old high school student from Jabalpur, India who was disappointed to learn that MITx had no plans to offer the follow-up class to 6.002x. Typically, the next class students take at MIT is 6.003, Signals and Systems. So Bhave took matters into his own hands, creating his own open online course with help from two other members of the 6.002 learning community – a class based on a blend of MIT OpenCourseWare and student-created materials.”

![]() ”Taking matters into your own hands” (and “taking learning into your own hands”) is one of the most empowering things that the MOOCs can offer. But while they do offer the chance for anyone to sign up and learn, the ease with which you can drop in is echoed in the ease with which you can drop out.

”Taking matters into your own hands” (and “taking learning into your own hands”) is one of the most empowering things that the MOOCs can offer. But while they do offer the chance for anyone to sign up and learn, the ease with which you can drop in is echoed in the ease with which you can drop out.

And there’s a lot of dropping out. Sue Gee highlighted this in her post “MITx — The Fallout Rate” with some statistics about the completion rate of its first offering: over 150,000 sign-ups; 7,157 certificates awarded at the end of the class — a 5% pass rate (that compares to a roughly 14% pass rate for Sebastian Thrun’s Stanford AI MOOC). Of those 150,000 signups, just 69,221 people looked at the first problem set. Of those, just 26,349 earned at least one point on the first problem set. 13,569 people looked at the midterm, 10,547 people got at least one point it, and 9,318 people got a passing score. 10,262 people looked at the final exam,, 8,240 people got at least one point on it, and 5,800 people got a passing score.

Looking at the numbers for Coursera’s Social Network Analysis class, Alan Levine notes a similar drop-off. 61,285 students registered. 1303 (2%) earned a certificate. 107 earned "the programming (i.e. ‘with distinction’) version of the certificate (0.17%).” He writes,

So in the end, we have 107 students who got the more personalized attention (doing a project, getting feedback, being part of the Google hangout presentations).

This class had one professor and 3 TA, about a 1 : 27 teacher/student ratio.

That is pretty much the size of a normal section of a class, it is the size of one of our ds106 sections at UMW.

Now there are a whole raft of reasons why people do not get to this end of the pipe, many, like in my case, fall on my own lack of drive to really push this up the hierarchy of where I put my attention.

But I submit the methodology of this course too has a large influence as well – it did not hold the attention of the bulk of its students, like 98% of them.

Let me repeat, 98% of the people who signed up for this course did not get the certificate, or 60,059 people. NOW THAT IS MASSIVE (as in hemorrhaging).

Yet the bulk of the hyper and fervor on MOOCs is the massive numbers of enrollments whichm, frankly, when you look at these numbers, it is the wrong end of donkey (to quote Neil Young), or maybe in this case… MOOcows.

Someone ought own those numbers coming out the end.

As for me, I signed up for the following MOOCs this year: Udacity CS 101 (my review here), Coursera CS 101 (my review here), Udacity Introduction to Statistics, Coursera Fantasy and Science Fiction, Coursera Modern and Contemporary Poetry, Ed Startup 101 (my posts here, here, here, here, and here), Mechanical MOOC, Google’s Search MOOC, Coursera Social Network Analysis, edX 6.00x, LAK12, CCK12, Instructional Ideas and Technology: Tools for Online Success, MOOC MOOC, and Coursera Internet History.

I only completed one.

Unbundling (and Rebundling) the University

But let’s not make too much over my willingness to sign up for classes and drop out, right? As I note in my Twitter bio, I’m a serial dropout. Lifelong learner, sure. But a serial dropout nonetheless.

Indeed, much of the hullaballoo about MOOCs this year has very little to do with the individual learner and more to do with the future of the university, which according to the doomsayers“will not survive the next 10 to 15 years unless they radically overhaul their current business models.”

But what are the business models for MOOCs? (Other than raising venture capital, of course.) That’s still a little unclear. In an article in The Chronicle of Higher Education in July, Jeffrey Young points to a couple of possibilities: selling courses to community colleges, charging tuition, and offering “secure assessments.” Young’s article cites Coursera founder Daphne Koller who says that “Our VC’s keep telling us that if you build a Web site that is changing the lives of millions of people, then the money will follow.”

“Basically Daphne Koller has conceded all agency to Venture Capitalists,” Jim Groom responded in a post called “We’ve been MOOCed” (featuring one of the best MOOC-related animated GIFs of the year). “When your business plan sounds like the catch phrase of a bad Kevin Costner movie that should raise some red flags.”

Red flags have been strewn all over the place this year as universities and professors and administrators and Boards of Trustees and venture capitalists and entrepreneurs have responded to the MOOC hype. Despite all the talk that "this changes everything," there are still so many unanswered questions: What happens when we outsource public education to for-profit companies? What about cheating? What about labor issues? What about intellectual property? What about cultural imperialism? What about licensing? What about open education and OER? How will universities fund upper division classes if the lower division ones (the ones that typically subsidize an entire department) can be taken online for free? What about credits ? Who counts as a “superstar professor”? What will be the attraction of the on-campus experience in the face of all these MOOCs? What is the future of higher ed?

The response to that last question by some is to contend that the future involves the “unbundling” of higher education. That is, the various services offered by the university — content delivery, assessment, credentialing, research, mentorship, affiliation and networking, job placement — will no longer all be monopolized by it. Other institutions and businesses will compete with higher education and will also offer these services.

![]() But as we see some of the unbundling start to occur, it feels as though there is a re-bundling of sorts. That is because, as Foucault would tell you, it is not simply a matter of “revolutionizing” the university and dismantling its “monopoly” on knowledge transfer and credentialing and then BOOM educational access and liberty and justice for all. Power is far more complex than that. As we unbundle assessment from the university, for example, it gets re-bundled with Pearson. As we unbundle the content from the campus classroom, it gets re-bundled with textbook publishers. With MOOCs, power might shift to the learner; it’s just as likely that power shifts to the venture capitalists.

But as we see some of the unbundling start to occur, it feels as though there is a re-bundling of sorts. That is because, as Foucault would tell you, it is not simply a matter of “revolutionizing” the university and dismantling its “monopoly” on knowledge transfer and credentialing and then BOOM educational access and liberty and justice for all. Power is far more complex than that. As we unbundle assessment from the university, for example, it gets re-bundled with Pearson. As we unbundle the content from the campus classroom, it gets re-bundled with textbook publishers. With MOOCs, power might shift to the learner; it’s just as likely that power shifts to the venture capitalists.

“Will MOOCs spell the end of higher education?” more than one headline has asked this year (sometimes with great glee, other times with great trepidation). As UVA’s Siva Vaidhyanathan recently noted, “This may or may not be the dawn of a new technological age for higher education. But it is certainly the dawn of a new era of unfounded hyperbole.” The year of the MOOC indeed.

![]()

Like many people, I spent Election Night tuned in to Twitter, watching the results via my social media stream rather than via television. It felt more participatory than passive. It felt more immediate, less contrived.

Like many people, I spent Election Night tuned in to Twitter, watching the results via my social media stream rather than via television. It felt more participatory than passive. It felt more immediate, less contrived.

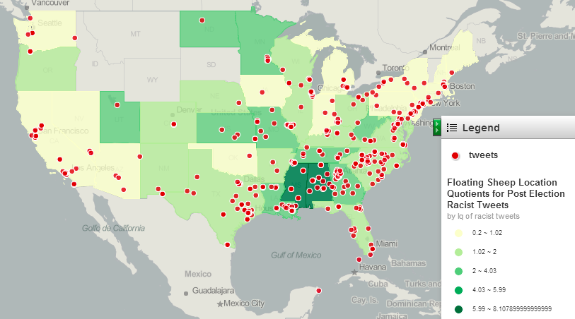

It’s hard not to view the listing of teens’ names, schools, and sports teams as appealing to the “justice” of the Internet -- indeed, the headline suggests the teens be "forced to answer" for their racist tweets. But by calling the teens’ principals and by invoking their various student handbooks, the Jezebel article also appeals to schools’ rules and Codes of Conduct. Internet justice meets institutional justice -- or something like that.

It’s hard not to view the listing of teens’ names, schools, and sports teams as appealing to the “justice” of the Internet -- indeed, the headline suggests the teens be "forced to answer" for their racist tweets. But by calling the teens’ principals and by invoking their various student handbooks, the Jezebel article also appeals to schools’ rules and Codes of Conduct. Internet justice meets institutional justice -- or something like that. Early last year, I predicted 2011 would be The Year of the Educational Tablet. I was wrong. It was The Year of the iPad. 2012 hasn’t turned out to be too shabby for Apple either. The company became

Early last year, I predicted 2011 would be The Year of the Educational Tablet. I was wrong. It was The Year of the iPad. 2012 hasn’t turned out to be too shabby for Apple either. The company became  When I covered this trend in 2011, I identified the tension between the rapid adoption of social networking in education (best exemplified perhaps by

When I covered this trend in 2011, I identified the tension between the rapid adoption of social networking in education (best exemplified perhaps by  I chose “text-messaging” as a trend last year when I could have just as easily selected “mobile learning” as the thing to focus on. And in hindsight, I do see lots more excitement for the latter than the former. Nevertheless, I still believe we ("we" Silicon Valley-focused tech bloggers in particular) underestimate the importance of SMS, particularly for teens and for the developing world.

I chose “text-messaging” as a trend last year when I could have just as easily selected “mobile learning” as the thing to focus on. And in hindsight, I do see lots more excitement for the latter than the former. Nevertheless, I still believe we ("we" Silicon Valley-focused tech bloggers in particular) underestimate the importance of SMS, particularly for teens and for the developing world.

It’s fascinating to re-read the post I wrote this time last year about the business of ed-tech. In it, I noted the founding of ed-tech news site

It’s fascinating to re-read the post I wrote this time last year about the business of ed-tech. In it, I noted the founding of ed-tech news site

Learning is not a product. It’s a process.

Learning is not a product. It’s a process.

“Flipping the classroom” is hardly new. But with all the hype surrounding both

“Flipping the classroom” is hardly new. But with all the hype surrounding both  There’s

There’s

In retrospect, it’s not surprising that 2012 was dominated by MOOCs as the trend started to really pick up in late 2011 with the huge enrollment in the three computer science courses that Stanford offered for free online during the Fall semester, along with the announcement of

In retrospect, it’s not surprising that 2012 was dominated by MOOCs as the trend started to really pick up in late 2011 with the huge enrollment in the three computer science courses that Stanford offered for free online during the Fall semester, along with the announcement of  Back to Cormier, the guy who coined the term “MOOC” back in 2008, long before Stanford’s massively-hyped online artificial intelligence class. That’s an important piece of education technology history that’s been overlooked a lot this year as Sebastian Thrun and his Stanford colleagues have received most of the credit in the mainstream press for “inventing” the MOOC.

Back to Cormier, the guy who coined the term “MOOC” back in 2008, long before Stanford’s massively-hyped online artificial intelligence class. That’s an important piece of education technology history that’s been overlooked a lot this year as Sebastian Thrun and his Stanford colleagues have received most of the credit in the mainstream press for “inventing” the MOOC. While a lot of the mainstream press’s attention to MOOCs has focused on the content, the class sizes, and the (potential) credentials,

While a lot of the mainstream press’s attention to MOOCs has focused on the content, the class sizes, and the (potential) credentials,  ”Taking matters into your own hands” (and “taking learning into your own hands”) is one of the most empowering things that the MOOCs can offer. But while they do offer the chance for anyone to sign up and learn, the ease with which you can drop in is echoed in the ease with which you can drop out.

”Taking matters into your own hands” (and “taking learning into your own hands”) is one of the most empowering things that the MOOCs can offer. But while they do offer the chance for anyone to sign up and learn, the ease with which you can drop in is echoed in the ease with which you can drop out. But as we see some of the unbundling start to occur, it feels as though there is a re-bundling of sorts. That is because, as Foucault would tell you, it is not simply a matter of “

But as we see some of the unbundling start to occur, it feels as though there is a re-bundling of sorts. That is because, as Foucault would tell you, it is not simply a matter of “ I am halfway through my year-end series on the

I am halfway through my year-end series on the