Disrupting Higher Education, Trinity College (Storified)

Hack Education Weekly News: MOOC Joiners, MOOC Quitters, and More

MOOCs

MOOCMOOCMOOCMOOCMOOCMOOCMOOCMOOCMOOCMOOCMOOC and so on...

UC Irvine professor Richard McKenzie left his Coursera-run economics MOOC mid-stream this past week “because of disagreements over how to best conduct this course,” reports The Chronicle of Higher Education. According to the article, a UC Irvine dean said those disagreements stemmed from the professor’s “reluctance to loosen his grip on students who he thought were not learning well in the course.” Tweets from students in the class add another dimension to story — storified here. The course is continuing without him.

FutureLearn, the UK’s MOOC platform, announced that it’s expanding the number of university- and organization-members, with the universities of Bath, Leicester, Nottingham, Queen’s Belfast and Reading all joining, along with the British Library. [Insert Fathom joke here…]

6.003z, the learner-run MOOC created as a follow-up to the MITx class 6.003x (and one of my favorite education startups of 2012), is preparing to run again this spring.

edX, the non-profit MOOC platform funded initially by MIT and Harvard, announced a major expansion this week, adding six new schools to its consortium: The Australian National University (ANU), Delft University of Technology, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), McGill University, the University of Toronto, and Rice University. According to documents obtained by The Chronicle of Higher Education, edX plans to offer participating institutions two choices regarding revenue-sharing: one based on a self-service model and one based on an “edX-supported model.” It’s still not clear, however, where exactly this “revenue” is going to come from.

Coursera also added more universities — 29 new ones — to its MOOC platform this week: California Institute of the Arts, Case Western Reserve University, Curtis Institute of Music, Northwestern University, Penn State University, Rutgers University, UC San Diego, UC Santa Cruz, UC Boulder, University of Rochester, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, University of Wisconsin Madison, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Tecnológico de Monterrey, Ecole Polytechnique, IE Business School, Leiden University, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat Muenchen, Sapienza University of Rome, Technical University Munich, Technical University of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, University of Geneva, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, National Taiwan University, National University of Singapore, and University of Tokyo.

Shocking, I realize, but some other non-MOOC-ish things happened too…

Making the Grade… Or Not

Judge Emil Giordano ruled this week that there was no breach of contract in the case of Lehigh graduate student Megan Thode and that, as such, she was not eligible for the $1.3 million in damages that she’d claimed, stemming from the C+ grade she got for a class.

Johns Hopkins University professor Peter Fröhlich grades on a curve, whereby he gives the student(s) with the highest mark on an exam 100% of the points. It’s been the “most predictable and consistent way" of assessing students’ work, he says. Until now. The students in his fall classes all boycotted the final exam, and hence the zero points they received became the highest score — they all received full marks. He’s changed his grading policy now, but kudos to him for honoring it in the first place — and a big thumbs up to the students who hacked his system.

Launches and Upgrades

The test-prep company Kaplanannounced that it was launching an ed-tech startup accelerator program in NYC, in partnership with Techstars. Techstars will invest $20,000 in the startups accepted to the program, who’ll get office space, access to the "Kaplan Way for Learning” proprietary program, and mentorship from “industry leaders” — a bunch of entrepreneurs and investors but according to the press release at least, not a single educator.

Pearson also announced that it was launching an ed-tech startup accelerator program in NYC. No funding involved with this one, although Pearson says it will mentor the startups (yay?) and then send them to London for a demo day (wheee.)

It’s time once again for the Microsoft-sponsored Imagine Cup, a student technology competition. Microsoft has doubled the cash prize amount this year and has also launched several awards aimed specifically at women developers: the Women’s Empowerment Award and the Women’s Athletics App Challenge.

Wordpress.com unveiled a new education vertical to encourage teachers to use the blogging platform. (Nicely timed with the news below, I guess…)

Downgrades and Closures

Twitter announced this week that it was closing down Posterous, a microblogging platform that it acquired last year. You have until April 30 to pull out your data before everything — about 4 million blog posts, links, and so on — goes kaput. Pro tip: if you are now considering moving from Posterous to Tumblr, you’re doing it wrong.

Oxford Universityannounced this week that it was blocking access to Google Docs, stating that the tool had been used in a series of phishing attacks. While the shut-down only lasted a couple of hours, it served to highlight increasing cybercriminal activity (and concerns about cybercriminal activity).

Funding

Celly, one of my picks for the best education startups of 2011, announced this week that it’s raised $1.4 million in funding. Celly, which provides a safe text-messaging service for schools (and for other community organizations), also released a free iPhone app.

Quad Learning announced that it has raised $11 million in funding. The company is building a national network of honors programs at the community college level.

Tutorspree, which as the name suggests offers a platform for finding tutors, has raised $800,000 in a Series D round of investment, reports Techcrunch.

BrightBytes, a startup that helps schools measure whether or not technology is affecting student achievement, has raised $750,000 in funding from Learn Capital, New Schools Venture Fund, and, according to Techcrunch, “an unnamed ‘strategic investor in the education sector.’”

Student Loan Hero, described as a “Mint.com for student loans” has raised $100,000 in funding. Not much. But enough for a press release and a Techcrunch story. So there’s that.

Stanford became the first university to raise over $1 billion from donors in a single year, according to the Council for Aid to Education. Although charitable giving to universities did increase between 2011 and 2012, it still hasn’t returned to pre–2008, pre-recession levels.

The Washington Post reported a fourth quarter loss of $45.4 million and took a $111.6 million write-down of Kaplan Test Prep. So there are some great lessons there, I’m sure, if you plan to join the Kaplan ed-tech incubator program, right?

Bad Metaphors and Ugly Examples

The Three-Fifths compromise was a good example of how compromise has helped the US “to form a more perfect union.” — Emory University President James Wagner.

"Education is the Afghanistan of technology.” — Google’s Peter Norvig.

Accountability rules will mean “higher ed will go jihahi” — anonymous “insider.”

Research and Data and Other Numbers-Related News Items

Teacher job satisfaction has reached a 25-year low, according to the 29th annual MetLife Survey of the American Teacher.

AP scores are up— with the highest percentage ever receiving a score of 5 — and more students are taking the test, according to data released by the College Board, which is good news for the College Board, errrrrr, I mean good news for students. Or for schools. Or something.

Non-US students perform better on the quantitative section of the GRE than do US students, says the Educational Testing Service. Cue the “schools are broken” meme.

According to a study conducted by Columbia University’s Community College Research Center, “students in demographic groups whose members typically struggle in traditional classrooms are finding their troubles exacerbated in online courses.”

Khan Academy bragged this week that it has recently surpassed one billion problems answered on its platform. “Why would students voluntarily complete one billion math problems?” Shantanu Sinha, the president of Khan Academy, wrote in a Huffington Post piece. Um, this Storify, gathered from students’ tweets, might give you some idea.

More and more jobs are requiring applicants have a college degree, even for positions that haven’t traditionally called for one, according to a story in The New York Times.

A study appearing in the Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education finds that college students continue to prefer print textbooks over digital ones. Some of the reasons: print offers fewer distractions, is easier to highlight and annotate, and offers better accessibility (h/t Nick Carr).

Photo credits: Keven Law

Who Owns Your Education Data? #ETMOOC

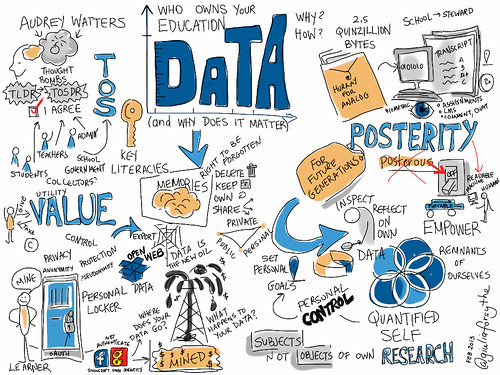

I have given a number of talks lately on this topic: who owns education data? (And will give a couple more next week -- on a panel at SXSWedu and then, a related but expanded version as a keynote at WebWise.)

I'm not sure why the topic has resonated so deeply with me lately -- perhaps it's all the talk outside the ed-tech sector about the promises of big data; perhaps it's the metaphor of mining vis-a-vis data mining; perhaps it's this new obsession with becoming "data-driven" that I hear politicians posit for schools and students (and thus all the ed-tech products that follow suit); perhaps it's that I am both intrigued and concerned by the emerging field of learning analytics; perhaps it's because I continue to be frustrated by our lack of attention to terms of service and to control of our content (which is data); perhaps it's that I struggle with thinking through exactly how to navigate the personal and the public demands for sharing education data.

Anyway, last night I facilitated a session as part of ETMOOC, a MOOC about education technology and media, organized by Alec Couros. Here's a link to the webinar recording and a link to my slides, along with the wonderful visual notes taken by the even-more-wonderful Giulia Forsythe.

Image credits: Giulia Forsythe

Hack Education Weekly News: Coding, Sequestration, and a School in the Cloud

Politics

It’s March 1. Cue the sequestration, across the board budget cuts because our “leaders” in Washington DC can’t do their jobs. The White House has released a state-by-state breakdown of how this will impact people and programs, which as education reporter Emily Richmond points out, will overwhelmingly impact the poorest schools and the most vulnerable students — an estimated $725 million cut to Title I programs and $600 million in special education funding.

Meanwhile, instead of actually addressing this budget impasse, the House of Representatives opted to pass a resolution creating a nation-wide content encouraging students to build mobile apps. No rules for the contest established yet. The amount of any prizes also remains undecided. But hey, STEM legislation! That’s a win for the future of America, right? (Ugh.)

The Oklahoma legislature passed the HB 1674, the Scientific Education and Academic Freedom Act this week (or as Esquire called it, the “Dare To Be Ignorant Protection Act of 2013,” which prevents schools from penalizing students for their stances on “controversial” science topics like global warming and evolution.

The governor of São Paulovetoed legislation that would have established a policy of OER in Brazil’s wealthiest state.

Massachusetts state representative Carlo Basile has sponsored a bill that would ban the mining for commercial purposes of any K–12 student data stored in or processed by cloud computing services. The wording in the law, as well as in this Wired write-up about it, certainly sounds like it’s aimed at Google but could have much more sweeping consequences depending on how “mining” and “commercial purposes” are defined.

Money continues to pour in to the Los Angeles Unified school board race: $1 million from New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg and $250,000 from former DC Public Schools Chancellor Michelle Rhee. “It’s for the sake of the children,” I’m sure.

Lawsuits

Apple has settled a lawsuit over “bait apps,” games that are free but then offer in-app purchases. Apple was sued by parents who found that their child racked up hundreds of dollars in charges from these apps. (See the Daily Show’s investigation into this practice.) As part of the settlement, Apple will offer $5 credits to those who claim that a minor bought an in-app item.

Accreditation… Or Not

The Higher Learning Commission, the regional agency that accredits the University of Phoenix, has recommended that the institution be put on probation. According to The Wall Street Journal, “probation was recommended after a review team concluded the University of Phoenix has ‘insufficient autonomy’ from Apollo, its parent company and sole shareholder, that complicates the board’s ability to manage the institution and maintain its integrity.”

Learn to Code

You should learn to program, say a bunch of CEOs, rockstars and ball players in a destined-to-be-viral video, many of whom have probably not committed a line of code in a very long time. But hey! Fame! Rockstar status! A job at a place that has video games and catering! Wheeee! More details via the newly launched organization Code.org.

Launches and Other Reasons to Issue a Press Release

The College Board has announced that it plans to redesign the SAT. No big surprise here as the new head of the College Board is David Coleman, the architect of the Common Core State Standards.

The data infrastructure inBloom (that I recently covered here) announced this week that it’s formed a strategic partnership with LearnSprout, one of my picks for the best education startups of 2012.

ShowMe, maker of an interactive whiteboard iPad app, has launched a Kickstarter campaign to fund a new app it’s building called Markup, which will enable teachers to grade (essay) assignments (with a stylus) on an iPad.

Khan Academy has issued a press release heralding the “first statewide pilot” of its program. The state in question, Idaho, where the “‘Rebooting Idaho Schools Using Khan Academy” grantees will collectively receive nearly $1.5 million for training, technology, technical assistance and assessment from the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Foundation.”

Apple issued a press release this week, touting that its iTunes U has now had over 1 billion downloads. The company also told All Things D that it’s sold 4.5 million iPads to U.S. schools and told Techcrunch that it’s sold 8 million iPads to schools worldwide.

It’s a much smaller number, but I confess, it’s one that makes me happier: Raspberry Pi says that it’s sold 1 million units of its credit-card sized computer since its launch a year ago. Happy birthday, Raspberry Pi, and hooray for those who’re using this tool to help kids learn to hack and build with technology, not just consume it.

The New Orleans-based education accelerator program 4.0 Schools is now taking applications for its next cohort. Deadline is March 13.

Funding and Fiscal Results

TED awarded its $1 million prize to Dr. Sugata Mitra for his “School in the Cloud” idea. See my rant on Twitter for my concerns — questions that I’m just too tired to re-write here. (It’s been an exhausting week.)

The math MMO startup Sokikom announced that it has raised $2 million in funding, half of that from a grant from the Institute of Education Sciences (a research branch within the U.S. Department of Education) and the other half from former Intel CEO Craig Barrett and Zynga co-founder Steve Schoettler.

The learn-to-code startup Thinkful has raised $1 million in funding from Peter Thiel’s FF Angel, RRE Ventures, Quotidian Ventures and others. The company’s founders, Darrell Silver and Dan Friedman, were recipients of the 20 Under 20 Thiel Fellowship. More on the startup at GigaOm.

Kickboard, a startup that offers schools and teachers a dashboard for academic and behavioral data, has raised $2 million in investment.

Textbook and testing giant Pearson released its 2012 financials this week. Among the results, its North American Education revenues were up 2% “in a year when US School and Higher Education publishing revenues declined by 10% for the industry as a whole.” And “International Education revenues up 13% with emerging market revenues up 25%.”

Interactive whiteboard maker Promethean Worldreleased its annual financials too. Revenues fell 29.4%, resulting in a pre-tax loss of £165.4 million (versus the company’s £16 million profit in 2011).

Barnes & Noble also posted fiscal results this week — losses in its third quarter (particularly bad news since that covered the holiday season). The losses were particularly felt in the company’s Nook division, falling 25.9% to $316 million. That division saw investment last year by Pearson and Microsoft, so we’ll see what happens as the company crumbles.

Research and Data

The Pew Internet and American Life Project released the results of its survey of National Writing Project and Advanced Placement teachers: “How Teachers Are Using Technology at Home and in Their Classrooms.” Among the findings (and I recommend reading the whole report and not just the few stats that are pulled out in the overview): 54% of respondents said that all or almost all students had sufficient access to digital tools at school. Just 18% said that students had sufficient access at home. The survey population isn’t typical of all teachers, I don’t think, and it’s certainly more tech savvy than the “average” adult Internet user — creating more content, owning more gadgets, and so on.

Mathematica Policy Research released the results of its latest study commissioned by KIPP, the “Knowledge is Power Program” chain of charter schools. The study examines 5 years worth data from 43 KIPP schools and concludes that “the average impact of KIPP on student achievement is positive, statistically significant, and educationally substantial.” Recommended reading: Bruce Baker’s analysis of the study and its “non-reformy lessons.”

New data from Georgetown’s Center on Education and the Workforce on community college degrees and career and technical education. CNN goes with the headline and factoid that nearly 30% of Americans with associate’s degrees now make more than those with Bachelor’s. Of course, the area that degree is in matters. Yes, a two year degree in nursing might be a more lucrative option than a four year degree in art history. Duh.

OU grad student Katy Jordan is tracking the completion rates across the various MOOC courses and platforms (those that make the data publicly available, that is). Really interesting stuff here, and while much of the emphasis continues to be on that very low rate of completion (on average, it’s less than 10%), I think there are other insights to be gleaned here as well: does robot-grading versus peer-grading make a difference? Does the subject matter or level make a difference? Too bad the "open" in these MOOCs doesn't include being more transparent about this and other data, and kudos for Jordan for doing the research here.

Awards

Congratulations to Colin Woodward, winner of the 2012 George Polk Award for Education Reporting for his story “The profit motive behind virtual schools in Maine.”

Photo credits: s2art

Hacking at Education: TED, Technology Entrepreneurship, Uncollege, and the Hole in the Wall

Last week as part of its glitzy annual conference in Long Beach, California, TED awarded its $1 million prize to Sugata Mitra to support his wish to build a “School in the Cloud,” a self-organized learning environment based on his “Hole in the Wall” and “Granny Cloud” research.

Next week Pearson, the largest and most powerful education company in the world, will publish Dale Stephens’ book Hacking Your Education: Ditch the Lectures, Save Tens of Thousands, and Learn More Than Your Peers Ever Will, a personal experience narrative and guide about dropping out of college and making it in Silicon Valley.

Both these projects — the Hole in the Wall and the Uncollege movement — claim to “hack education” on behalf of the learner. And both have been the topics of TED Talks — on the main TED stage and at the smaller TEDx spin–offs.

Mitra’s TED talks, which have been particularly successful, describe his company’s placing of computer kiosks into the slums of India. From there, street children have gained computer and English literacy skills without adult intervention.

It’s an story that Stephens nods vigorously at: the self-directed and self-motivated student can learn anything; no thanks to our testing-dominated public school curriculum; no thanks to our federally-subsidized, loan-obsessed university; but thanks to the Internet and the growing availability of open online resources -- thanks to the access and a lot of “grit.”

In the TED world of techno-humanitarianism, this computer-enabled learning certainly makes for an incredibly compelling story.

But once something becomes a TED Talk, it becomes oddly unassailable. The video, the speech, the idea, the applause — there too often stops our critical faculties. We don’t interrupt. We don’t jeer. We don’t ask any follow-up questions.

They lecture. We listen.

The phrase, “child-driven education” — promoted by Sugatra Mitra and Dale Stephens and others — is a stirring one. It’s a good slogan, as all popular TED talks are wont to be.

It’s one that posits that all children are capable learners — no manner race nor creed nor gender nor income; it’s one that posits that knowledge need not be delivered by teachers nor learning spaces be teacher-centered. Hail discovery, curiosity, inquiry and such.

This new vision for education, as Mitra explains it, can be enabled now thanks to computer technologies. “The future of learning” will be a break from the present and the past — from our current education system’s factory model and its colonial legacy.

“I tried to look at where did the kind of learning we do in schools, where did it come from? And you can look far back into the past, but if you look at present-day schooling the way it is, it’s quite easy to figure out where it came from. It came from about 300 years ago, and it came from the last and the biggest of the empires on this planet. [“The British Empire”] Imagine trying to run the show, trying to run the entire planet, without computers, without telephones, with data handwritten on pieces of paper, and traveling by ships. But the Victorians actually did it. What they did was amazing. They created a global computer made up of people. It’s still with us today. It’s called the bureaucratic administrative machine. In order to have that machine running, you need lots and lots of people. They made another machine to produce those people: the school. The schools would produce the people who would then become parts of the bureaucratic administrative machine. They must be identical to each other. They must know three things: They must have good handwriting, because the data is handwritten; they must be able to read; and they must be able to do multiplication, division, addition and subtraction in their head. They must be so identical that you could pick one up from New Zealand and ship them to Canada and he would be instantly functional. The Victorians were great engineers. They engineered a system that was so robust that it’s still with us today, continuously producing identical people for a machine that no longer exists. The empire is gone, so what are we doing with that design that produces these identical people, and what are we going to do next if we ever are going to do anything else with it?

[“Schools as we know them are obsolete"]

So that’s a pretty strong comment there. I said schools as we know them now, they’re obsolete. I’m not saying they’re broken. It’s quite fashionable to say that the education system’s broken. It’s not broken. It’s wonderfully constructed. It’s just that we don’t need it anymore. It’s outdated. What are the kind of jobs that we have today? Well, the clerks are the computers. They’re there in thousands in every office. And you have people who guide those computers to do their clerical jobs. Those people don’t need to be able to write beautifully by hand. They don’t need to be able to multiply numbers in their heads. They do need to be able to read. In fact, they need to be able to read discerningly.”

Pardon my quoting Mitra’s TED Prize acceptance speech at length, but I always feel like it’s hard to get a word in edgewise in TED Talks. Indeed, they’re designed that way: well-scripted and highly-polished presentations — 15 to 20 minutes on “ideas worth spreading.” The audience is supposed to bask in the ideas — get carried away in the prose and in the delight of human curiosity and the superstar delivery and “why hadn’t I thunk of that” problem-solving.

You are not supposed to interrogate a TED Talk. You’re supposed to share the talk on Facebook.

But I have questions.

I have questions about this history of schooling as Mitra (and others) tell it, about colonialism and neo-colonialism. I have questions about the funding of the initial “Hole in the Wall” project (it came from NIIT, an India-based “enterprise learning solution” company that offers 2- and 4-year IT diplomas). I have questions about these commercial interests in “child-driven education” (As Ellen Seitler asks, “can the customer base be expanded to reach people without a computer, without literacy, and without any formal teaching whatsoever?”). I have questions about the research from the “Hole in the Wall” project — the research, not the 15 minute TED spiel about it. I have questions about girls’ lack of participation in the kiosks. I have questions about project’s usage of retired British schoolteachers — “grannies” — to interact with Indian children via Skype.

I have questions about community support. I have questions about what happens when we dismantle public institutions like schools — questions about social justice, questions about community, questions about care. I have questions about the promise of a liberation via a “child-driven education,” questions about this particular brand of neo-liberalism, techno-humanitarianism, and techno-individualism.

You don’t get to ask questions of a TED Talk. Even the $10,000 ticket to watch it live only gives you the privilege of a seat in the theater.

As Evgeny Morozov recently wrote in a review of several books published by the new TED press,

“Since any meaningful discussion of politics is off limits at TED, the solutions advocated by TED’s techno-humanitarians cannot go beyond the toolkit available to the scientist, the coder, and the engineer. This leaves Silicon Valley entrepreneurs positioned as TED’s preferred redeemers. In TED world, tech entrepreneurs are in the business of solving the world’s most pressing problems. This is what makes TED stand out from other globalist shindigs, and makes its intellectual performances increasingly irrelevant to genuine thought and serious action.”

Dale Stephens is not a tech entrepreneur. But as one of the first recipients of the 20 Under 20 Thiel Fellowship, the program that pays young men and women (well, mostly men) $100,000 to drop out of college to pursue their entrepreneurial visions, Stephens has been supported by one of the most powerful tech entrepreneurs and one of the world’s richest men: PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel.

Stephens’ and Thiel’s message about education overlap in many places, namely: “there is a higher education bubble.” That is, our investment in college education is overhyped and irrational, and now the cost of a diploma has out-stripped its value.

That’s the underlying argument of Stephens soon-to-be-released book Hacking Your Education: Ditch the Lectures, Save Tens of Thousands, and Learn More Than Your Peers Ever Will.

The book, along with Stephens’ larger speaking and writing efforts about unschooling, share with Sugata Mitra’s TED Talk the notion that we can and must support a learner-centered and learner-driven education future — something that universities in particular, Stephens argues, fail to do.

But this isn’t simply about the rise of the learner — we’d be so naive to believe that’s the case. It’s about the rise of the technology industry alongside the collapse of the education sector. Take away the public school, as Mitra suggests — it is a colonial legacy! — and replace it with computers. Something like NIIT Enterprise Learning Solutions, perhaps, “one of the top 5 training companies in the world.”

Stephens echoes those on the TED stage and those in Silicon Valley when he talks about the future of higher education thusly: “the advancement of technology means that educational institutions are being dismantled. … And just like that, the three major functions of a university—knowledge delivery, community building, and employer signaling—are replaced.”

Of course, to narrow “the university to these three “major functions” is, well, narrow. What about knowledge building? What about research? What about civics and service? What about the public good?

And let’s be clear here: this is a calculated view and one perfectly crafted for the intellectually impeccable TED stage, one that situates education institutions as attacked by the Internet, rather than as the co-creators of it; one that posits professors as necessarily resistors to change, rather than agents of innovation.

And framed as such, this signals a massive opportunity —a wink and a nod to those investors in the audience — for the tech entrepreneur. See also: the TED Talk by Salman Khan (2+ million views). The TED Talk by Coursera co-founder Daphne Koller (+900K views). The TED Talk by Sugata Mitra (1.2 million views).

Much like a TED Talk, Stephens’ book is neither designed nor prepared to be closely interrogated. He talks “big ideas” in sweeping generalizations. Stephens invokes anecdote after anecdote, hoping I suppose that this blurs into data. But while “uncollege” might make a good slogan — particularly considering the high cost of tuition and the increasing burden of student debt — the advice in Stephens’ handbook doesn’t always stand up to close scrutiny.

“I’m the first MacCaw not to go to Cambridge,” says one of the informant. This and a myriad of other utterances are rather mind-boggling markers of privilege, markers that Hacking Your Education fails to examine and that the book seems extraordinarily unaware of.

One hack it offers for the young uncollege-er: “take people out for coffee” — budget $150 a month to do so. Another hack: “go to conferences.” Sneak in. “Hardly anyone will notice.” Another hack: “buy an airplane ticket.” “You can go anywhere in the world for $1500.” “Collect frequent flyer points.” Too bad if you’re big or black or brown or a non-native English speaker or the working poor or a single mom. Just practice your posture and your grammar and your email introductions, and you’re golden.

“You are responsible for your own successes and failures” according to Hacking Your Education. Systematic racism, sexism, classism be damned. Race, class, and gender privilege, family and community and mentor support — how much of “hacking your education” entails relying on this and not just on individual drive, curiosity, or “grit”? The book ignores all this. (Cue Peter Thiel’s libertarianism and Silicon Valley’s insistence that it is a meritocracy.)

Now don’t get me wrong. There’s plenty that education institutions do — from K–12 onward — that doesn’t help learners at all. Cost. Curriculum. Control. Assessments. Standardization. Debt. Unemployment. Existential Malaise.

Yet much of what’s written about in Hacking Your Education feels like a caricature of school, a convenient description of the failures of our modern education system that feels very particular to Stephens’ own biography, to the anecdotes told by his informants and — and here’s the most troubling part — to a larger political narrative about the “brokenness” and irrelevance of the public education system. “Think about it,” Dale writes, “in your twelve years of school did any teachers ever ask you what you wanted to learn, or did they just prepare you for the next test?”

Or “schools only teach what is settled.”

Or “university does not exist to train you for the real world—it exists to make money.”

These assertions can all be easily disputed, if no other reason than none of them are backed up with any evidence or research. And even the data the book does cite are flawed or contested, crafted to make a particular political point. The way that Stephens (and he’s certainly not alone in this) touts the findings in Academically Adrift— that college students don’t learn critical skills — without any recognition of the serious critiques about the book’s methodology, is a case in point.

Take too the claim that “When I started writing this book in 2011, the average student graduated with $25,000 or so in debt. By 2012, it was up to $27,000 in debt.” Not quite true. That might be the average for students who take out student loans; but only two-thirds of students do so. That means the average student loan debt is actually lower — and here’s the problem with mean versus median — skewed too by the very small percentage of borrowers (3.1%) who borrow over $100,000.

I’m quibbling here, perhaps. This isn’t a book grounded in education research. It’s a book grounded in personal experience: “Ditch the lectures, save tens of thousands, and learn more than your peers ever will.” Or, “Do what Dale did.” Drop out. Network. Travel. Profit.

And Stephens has been extraordinarily successful at this. He’s been successful as a (TED) speaker. As an op-ed writer. And now, as a Pearson-published author.

His book is not a TED book, but it shares with the Mitra's TED Talk that certain hope for virality and inscrutability. As Morozov writes,

Today TED is an insatiable kingpin of international meme laundering—a place where ideas, regardless of their quality, go to seek celebrity, to live in the form of videos, tweets, and now e-books. In the world of TED—or, to use their argot, in the TED “ecosystem”—books become talks, talks become memes, memes become projects, projects become talks, talks become books—and so it goes ad infinitum in the sizzling Stakhanovite cycle of memetics, until any shade of depth or nuance disappears into the virtual void. Richard Dawkins, the father of memetics, should be very proud. Perhaps he can explain how “ideas worth spreading” become “ideas no footnotes can support.”

Hacking Your Education advances the notion that education is a personal (financial) investment rather than a public good. The School in the Cloud project posits that education is a corporate (financial) investment rather than a public good. Why fund public schools when we can put a kiosk in a tech company’s annex? Why fund public schools when you can learn anything online?

The future that TED Talks paint doesn’t want us to think too deeply as we ask these questions. But what happens,when we “hack education” in such a way that our public institutions are dismantled? What happens to that public good? What happens to community? What happens to local economies? What happens to social justice?

As such, the vision for the future of education offered in Stephens’ new book is an individualist and incredibly elitist one. It contains a grossly unexamined exceptionalism, much like the Hole in the Wall which, at the end of the day, worked best for the strongest boys on the streets.

So despite their claims to be liberatory — with the focus on “the learner” and “the child” — this hacking of education by Mitra and Stephens is politically regressive. It is however likely to be good business for the legions of tech entrepreneurs in the audience.

Sugata Mitra, “Build a School in the Cloud,” TED, 2013. (link)

Dale Stephens, Hacking Your Education: Ditch the Lectures, Save Tens of Thousands, and Learn More Than Your Peers Ever Will, Perigee Trade, 2013. (Amazon Affiliate link)

The Weirdness of SXSWedu

“Keep Austin weird.” That’s been a long-time slogan of the Texas town, adopted by the local business and artist community. It's a slogan that has always worked well in conjunction with the annual SXSW festival.

I like that weirdness, Austin’s blend of indie, counter- and subculture traditions.

But when I say that SXSWedu was “weird” that’s not necessarily what I'm referring to at all. I don’t actually mean it was terribly “funky,” “eccentric,” or “offbeat.” In many ways, I found this week to be more like some of the word's other meanings: “strangely unsettling” and at times “disconcerting.”

After last year’s SXSWedu, I thought hard about whether or not I’d come back. But I figured that as it was only the event’s second year, I’d give it another shot; I’d do what I could to improve things rather than to simply shrug and walk away. I sat on the event’s Advisory Board (meaning I reviewed proposals as part of the SXSW Panel Picker process) for example.

One of my criticisms of last year’s event was that it felt very much like the Pearson show. Indeed Pearson was a major sponsor. Pearson’s then-CEO was a keynote. Pearson people seemed to be on a lot of panels, and many of those panels reflected topics Pearson clearly wanted discussed. Educators were in short supply at the event. (I remember one of the parties, where two educators went around the room asking who was a classroom teacher. At a jam-packed event, they could only find two others who were.)

Unfortunately both these issues — the corporate-driven conference agenda and the lack of educators — seemed to be exacerbated this year.

Weird Tensions

According to The Chronicle of Higher Education, however educators did make up 60% of the audience. (Those that I informally polled about this pegged the educator presence as between 20 to 40%.) No matter the actual figure, the perception here matters — “this isn’t an educator conference,” one person said to me — as does the sense among many attendees that there were two distinct tracks at SXSWedu: one for entrepreneurs and one for educators, and to quote Rudyard Kipling, “never the twain shall meet.” And sadly worse — they do meet, but the gulf between them becomes greater. Such things happen when teachers hear things like“learning outcomes matter — once we make money for our investors.”

The event’s director Ron Reed told The Chronicle that “Frankly, we like that tension” between entrepreneurs and educators. No doubt these tensions exist — we needn’t manufacture them and we shouldn’t try to obscure them. And sometimes these tensions can be used quite fruitfully, if — if— we recognize them and, as such, have the difficult conversations that we must among educators and industry folks. (Note: this does not mean simply using SXSWedu as an opportunity to corner some teachers as a focus group for your startup ideas.)

Weird Topics

It’s been a while since I reviewed panel proposals for SXSWedu, and I can’t remember any trends that really stuck out among those I looked at. But I thought the conference organizers did a pretty good job pulling together a program that covered a range of important topics and trends: MOOCs, Maker culture, gaming, entrepreneurship, data and analytics, and so on.

But with an inBloom lounge and an inBloom session track (in addition to the data track) and an inBloom party and an inBloom hackathon and lots of folks in inBloom t-shirts and a Gates Foundation party and a Bill Gates keynote… well, it felt pretty obvious what the agenda of SXSWedu was meant to be. Or rather whose agenda it was meant to be.

Return of the Weird?

Of course, event sponsorship is always awkward and frequently awful. And it’s rarely the panels or keynotes themselves that are the most rewarding at any conference. Rather it’s the hallway and dinner conversations. These are more likely when and where those difficult and productive conversations happen. I do appreciate that SXSWedu provided more physical spaces and allotted times to encourage this sort of thing; but I can’t help but think that a more unconference-y SXSWedu would be weirder, less scripted, less corporate, and as such mo’ better. Looking at what SXSW Interactive has become, however, I won’t hold my breath.

Like all events that I attend, it’s the people — face-to-face — that make the travel worth it. New friends. Old friends. People I haven’t seen since last year in Austin —that’s key and that could well be the makings of a nascent SXSWedu community. But it’s pretty damn nascent, and I do wonder how much damage that “tension” between educators and entrepreneurs and that obvious corporate agenda has done to it.

So will I go back next year? I don’t know. It depends on if you’re going. It depends on the major sponsor, and hence the keynote speaker. (I have my predictions already about who that’ll be. Do you?) And frankly I think it depends, a year from now, on how “weird” — “punk” weird or “puke!” weird — ed-tech has become.

Image credits: Jac de Haan

Whose Learning Is It Anyway? (WebWise 2013)

I gave the keynote today at WebWise 2013, and I have to say, after a long week at SXSWedu, I was pretty happy to be able to be around a bunch of librarians and archivists. The theme of this year's WebWise was "Putting the Learner at the Center," and my talk echoed something I've been pushing a lot lately: this question of who owns educational data. I was particularly eager to raise this question in front of this particular crowd, as I believe that IMLS-ish folks will be key in helping answer it. (No pressure, guys!)

Below is a rough transcript of my talk, along with a Storify of some of the tweets and a copy of my slides.

Whose Learning Is It Anyway?

Some of you might recognize the title of this talk as a nod to the TV program “Whose Line Is It Anyway?” — a show that ran for 8 seasons on ABC and which is apparently coming back to cable after a 10 year hiatus. Bonus points if this title conjures the British version of the show rather than the Drew Carey hosted one. Double bonus points if you think of the radio show that predated both.

“Whose Line Is It Anyway” was/is a comedy show — a game show, but only sort of — where the contestants had to compete in various challenges that tested their improvisational skills (as well sometimes as their skills in singing and impressions).

Improvisation is a particularly interesting form of comedy — an incredibly challenging but rewarding form of theater.

With improv, you must hold in your head as many cultural, historical, and literary references as you can. These must be quickly and readily accessible. Characters, themes, situations, voices, postures, gestures. Performers must be able to recall, remix, collaborate, innovate, pivot, and hopefully make the audience laugh.

Now this certainly sounds like a slew of tech-industry-related buzzwords doesn’t it – remix, collaborate, innovate, pivot — and as such, I’m sure there’s someone who might hear that and think “wow, let’s disrupt improv!” — this is a job for a database or an app: index it all, access it in real-time to maximize humor!

But can a computer do improv?

The Turing Test – the test to see if a machine is “intelligent” enough to fool a human – doesn’t necessarily help us here.

IBM’s AI machine Watson did appear on another game show after all — although on Jeopardy, not on Whose Line Is It Anyway?

Using far less sophisticated technology — as in something I can program — are Twitter bots, like the incredibly popular @horse_ebooks, that string together random phrases that look a bit like improv… And sometimes are funny. But unintentionally so.

I would contend there’s a difference here between the programmatic and the improvisational.

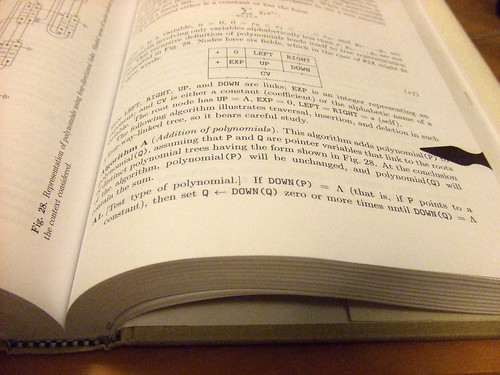

I’m currently working on a book on artificial intelligence and education technology — our decades long quest to build teaching machines — so I have been thinking a lot about these things lately: about how our increasing use of AI — a field that relies a great deal on machine learning — might shape what we think about human learning.

The idea for the book came to me when I was in one of Google’s self-driving cars, along with one of the car’s inventors, Sebastian Thrun. He explained to me as we zipped along interstate 280 all the cameras and sensors the car possessed — internally and externally — all the mapping data and all the traffic data that Google had amassed — how all of this going into building a car that does not need a human to steer it, to press on the brakes or the accelerator. In the future of self-driving cars, Thrun said, cars will move along the highway much more efficiently.

Now I confess, as someone who doesn’t drive and who recently moved to LA, I was thrilled with the idea of the robot cars.

But then I thought about Sebastian Thrun’s latest endeavors — the massive online startup Udacity — and I balked. “Wait, no!” I'm not too keen on the notion of automating education for the sake of efficiency.

I did wonder if it was simply me that was construing the self-driving car as a metaphor for education technology, or if this really was the model that the artificial intelligence used to think about our “learning journeys” if you will.

It’s worth pointing out that the three major MOOC initiatives — Udacity, Coursera, and edX — all have their origins in the AI lab. Daphne Koller, Andrew Ng, Sebastian Thrun, and are all AI professors at Stanford; Ng took over the head of Stanford’s AI lab when Thrun stepped down. Anant Agarwal, the head of edX, was the former head of MIT’s AI lab and a developer of exascale computing technology.

As such, these MOOC endeavors could be read as part of the long-running efforts on the part of AI researchers to develop automated teaching machines and intelligent tutoring systems.

If we just have enough data — from content to assessment data and sure, from the tens of thousands of students in massive online courses and all their keyboard and mouse clicks — we might be able to build algorithms and models that are “personalized” and “adaptive.”

But can that system ever really look like improv? Can it look like open inquiry? Can it look like self-driven learning?

If a tree falls in the road in front of a self-driving car, the car shuts down. It doesn’t go around it. It doesn’t take a different route. It stops. The self-driving car cannot handle that sort of serendipitous event.

Yet.

And here we move to the heart of the matter — from “whose line is it anyway?” to “whose learning is it?” And let’s start with the data — because certainly there are many systems — robot teachers and robot graders and adaptive apps and quizzes — being built on top of it.

Who owns the learning? Who owns student data? Who owns our education data after we’re out of school? Who owns learners’ data across the variety of institutions — formal and informal — where we continue to learn throughout our lives?

I posed that question on Twitter a week or so ago. Do students own it? Schools? The government? Software providers?

The answers were varied — some people insisted that education data belongs to the student; others insisted that it belongs to however collects it. The discrepancies, to a certain extent, no doubt reflect the different levels of awareness about and definitions of education data. What counts as education data – and I certainly don’t think it just means student test scores and student ID numbers.

And honestly, it’s probably not too hard to argue that our lack of a strong stance or understanding on this topic goes for all our digital data: who’s collecting it, to what end, under what legal protections or restrictions.

These questions aren’t entirely new, but our increasing use of technologies is creating lots of new data — and lots more data — some 2.5 quintillion bytes of data created every day according to IBM — and we are facing numerous challenges and opportunities as a society over what it means to control and access and — in our case here, I’d imagine — learn from it.

Yet the question of ownership of education data remains largely – and troublingly – unresolved.

A personal anecdote: a couple of years ago, my mum gave me a large manilla envelope full of my old schoolwork — drawings and writings and photos from as far back as preschool — some projects I remembered making, many I didn’t. Mostly the envelope contained administrative records — my report cards, various certificates of accomplishment, some ribbons.

That envelope was obviously a low-tech way to collect my school records. It is certainly my mother’s curation of “what counts” as my education data – as such, a reflection of proud parenting and of schooling in a pre-digital age, I suppose. Nonetheless I think the manilla envelope makes for an interesting metaphor — a model to think about storing education data, one with strengths and weaknesses and strange relevancies for our thinking about the digital documentation and storage of education data today.

What happens now that our schoolwork is increasingly “born digital”? Is there a virtualized equivalent to my mum’s envelope?

Or — and this is what I often fear — are we creating education-related content in apps, on websites, in learning management systems that we will only have temporary access to?

Once we put our content in, can we get our content out again — and out in a format that’s actually readable, by humans and by machines?

Another anecdote: last summer, I met a young girl whose school was piloting a one-to-one iPad program. This girl’s family weren’t particularly tech-oriented. They didn’t have a computer at home. So when the school offered them, at the beginning of the year, a chance to buy the iPad, they declined. It was expensive. They didn’t see the point. But by the end of the school year, their minds had changed — one of those stories that sounds at first glance like a PR win for Apple — the device was easy to use, the girl loved it, she’d downloaded some other apps, she’d created a lot of drawings and written a lot of stories with it. And so the family approached the school about buying the iPad. But it was too late, the school said. The purchasing opportunity was a limited one at the beginning of the year. And the iPad was returned — with all this girl’s data on it. There was no manilla envelope — physical or digital — for much of her 6th grade schoolwork.

The family had no home iTunes account with which to sync the student’s data — that’s what you’re “supposed” to do to get your data off an iPad. But even more troubling, schools tend to create “dummy” accounts for these devices. So even if you did have your own iTunes account at home, it wouldn’t matter. Your school device is registered to "student25@school.com."

We need to think about whether that’s the place we want to store all our data — all our kids’ data.

This isn’t just about Apple, of course. We must ask: Is there a safe digital place – any safe place– where we can store our school work and our school records — not just for the duration of a course or for the length of school year, but for “posterity”?

“Posterity” — why, that word sounds a lot like “Posterous,” doesn’t it. “Posterous” — the microblogging platform that was acquired by Twitter last year and that announced a couple of weeks ago that it would be shutting down at the end of April. Posterous — a free tool that many students and educators and librarians (among others) were using for sharing and storing writing, photos, video, and other digital content.

The impending closure of Posterous is hardly the first or the only time something like this has happened to a tool — free or paid – that’s been popular for educational purposes. Heck, we often demand students put their school work into a learning management system where they lose access to it at the end of the semester. And for that pleasure, schools spend hundreds of thousands of dollars.

So a shout-out here to the University of Mary Washington and its “Domain of One’s Own” initiative that gives domains, Web hosting, and technical training to faculty and students. As the name of the initiative suggests, students own their space on the Web. They own their own domain. They control it as students, they’re encouraged to use it as an electronic portfolio, and here’s the crucial point — they can take it with them when they graduate.

The impending demise of Posterous prompts us to ask — yet again: Are we storing our digital education content in a place that we actually control, that we actually own?

Do we — can we — own our education data? Whose data is it — whose learning is it?

While my manilla envelope might appear to offer better control over my educational content but that’s not necessarily the case.

The papers that I have in my possession are, in many instances, just a transcript. A copy. My schools retain the originals. Or I guess they do. Some of these report cards are decades old. Regardless — anyone who’s had to send money to their alma mater in order to request an official copy of their transcript has probably cursed this particular arrangement. “I earned those grades, dammit.” Give me my data.

The school retains my data, although according to FERPA (the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, the law that in the U.S. governs the privacy of educational records) that data is mine to review and correct. And according to FERPA, I have some say over who it’s shared with. As do, my parents, until I turn 18.

But despite its claims to protect the privacy of students’ records, nowhere does FERPA say that a student actually “owns” her or his data. Nowhere does it say that a school does either. At best, it would seem, the education institution is a steward for the “official education record” — responsible for its storage, its security, and its protection. And truth be told, the terms of “ownership” are mostly spelled out between individual schools and the databases and software they buy or license.

So let’s push this question further: what data exactly are schools and other education-related institutions stewards for? Just what’s on the transcript — that is, dates of attendance, major, and final course grades?

What about behavior records? Test scores? Individual assignments?

What about library check-outs? Gym visits? Sports records? Cafeteria and bookstore purchases? Minutes from student meetings? Times in and out of the dormitory?

What about all the data that is being collected on and generated by students? (I should clarify again here that when I say “data,” I don’t just mean numbers. Essays and photos and videos are data too.)

What about students’ search engine history? Learning management system log-ins and duration of their LMS sessions? Blog and forum comment history? Internet usage while on campus? Emails sent and received? Social media profiles? Pages read in digital textbooks? Videos watched on Coursera or Khan Academy or Udacity, along with if and where they paused it? Exercises completed on any of these platforms? Wikipedia visits. Wikipedia edits. Levels on Angry Birds? Keystrokes and mouse clicks logged?

(That last item is, along with biometric data, how Coursera says it plans to confirm students’ identities.)

Do students own this data? Do they control any of it? Can they access it? Download it? Review it?

And here’s a very important question: Are students even aware that this data is being collected?

And: Are they asked for their consent before it’s shared?

Now, none of this sort of data is included in the manilla envelope my mom gave me, quite obviously. But I think it’s worth asking if a digital version of that envelope — whatever long-term storage unit we devise for students’ education data — should include these sorts of things.

Now, I can’t deny: much of my interest in the manilla envelope my mom saved was simply nostalgic. There were good memories and bad memories and forgotten memories from my schooling, and I was grateful that my mum had saved all that paper, even though it was decidedly her record of me — the items that she had chosen to save for me.

And when we talk about protecting and preserving students’ educational content — making sure that it doesn’t disappear like all those Posterous blogs are about to — I think much of our concern is about maintaining that record for the future. Collection for the sake of recollection.

That differs — substantially at times — from collecting your data in order to control it. And that differs from collecting it in order to analyze it.

What insights could I glean about myself as a learner from the contents of my manilla envelope — things unknown and unreflected upon, pulled out of the forgotten drawings and scribbled passions of my childhood?

And how might those insights have differed if I was able to review this education data on a real-time and ongoing basis, not just 20-some-odd years later?

The ability to glean insights — in real-time or near-real-time — from students’ data is the cornerstone of the emerging field of learning analytics. And while there are certainly many obstacles to making use of the data that schools already collect about students — thanks to information silos that are both technological and departmental and political — the drive for better learning analytics — and there are both business and research cases will drive this — will make students’ data of increasing importance for all manner of education institutions.

So again, I ask, who owns our education data?

I’ve spent the better part of this week at SXSWedu where it was very clear that student data is of major interest to education companies. This certainly reflects a larger trend in the technology sector — all this buzz about “big data.”

There’s long been a saying among tech folks that “if you aren’t paying for the product, you are the product.” It’s often applied to free tools like Facebook and Google that do use your personal data to sell advertising. But with what’s becoming a more data-oriented world, we might have to admit that even if you are paying for the product, you’re still the product. Your data certainly is.

And companies that have long gathered data about all our transactions and demographics are starting to sift through all that data — in order to improve the product, in order to improve the marketing, in order to beat their competition. There’s a sense — and the metaphor here is pretty horrible if you stop to think about it — that data is the new “oil” and our lives are set to be mined with the value extracted from them. How can we make sure that value stays with us?

Many of the panels at SXSWedu addressed education data (not this question of who owns it — the question of what to do with it, I should add), not surprisingly since one of the major sponsors of the event was inBloom, a new data infrastructure project that’s been funded by a $100 million investment by the Gates Foundation and built by the News Corp-owned Wireless Generation.

inBloom plans to build a centralized database of educational data, arguing — and this is true — that schools’ data infrastructure is woefully out of date and that data is often siloed in various apps and student information systems. But inBloom isn’t just pulling in the data typically contained in a student information system — that is, your name, your grade, your grades. This database will include health care records, behavioral records, and much much more.

The promise: to make learning more personalized and more adaptive. The vision: to build a platform that other third-party software providers can build upon and that schools and perhaps other learning institutions too can utilize.

When I asked Twitter “who owns your education data?” one of the responses was “it doesn’t matter.” The data “has no value except to those who take positive steps to use it.” Framed this way, it doesn’t matter if a student or a school or a software provider or a governmental agency owns the data, as long as its usage is beneficial. Certainly this is the promise of learning analytics: to enhance student outcomes, to boost student retention, and to increase course completion.

Now I won’t argue that these are “positive” uses for students, nor that students don’t want these things for themselves.

But if students do not own and do not control their data, then I fear (again) that data and analytics will be something we do to students, rather than do for them or do with them. Or — and here’s a radical notion — that we enable students to do for themselves.

I think this is why, for me, the “quantified self” movement seems an appealing and important development, not just for how we think of education data but for how we think of all the types of data that we currently create: on social media sites, on blogs, with our smartphones, with personal body sensors, with our credit cards, with our geolocation, with our searches and transactions and clicks.

A “quantified self” movement within education implies personal ownership and certainly demands personal control over data. As such, it requires setting personal goals. It requires a personal definition of “learning.”

It would also require a certain familiarity with the technologies that students utilize; it would require, one would imagine, an understanding of retrieving data and building data visualizations. It would require we read the Terms of Service and avoid applications with onerous ones.

These are all good things, I’d say, empowering things for students — for all of us truthfully — all with the goal of making us subjects and not just objects of technology and research and data.

If we build, then, that virtual version of my mum’s manilla envelope — in the service of not just long-term personal content storage but real-time personal learning analytics — it would demand that many things change in how we think about education data today.

Data would need to be portable; it would need to be interoperable. It would need to be human- and machine-readable — in other words, my transcript shouldn’t just be available on a watermarked piece of paper, my assignments not just stored in a PDF. It would mean that education data could no longer be stuck in silos — on or offline. The storage unit — let’s call it a personal data locker, with a nod to the Locker Project — would need to be sustainable – temporally, technologically, financially. It would need to follow a student throughout her or his school career, and ideally include informal as well as formal learning data. The locker would need to be extensible — that is, apps and visualization tools would be able to be built on top of it.

And the contents of the data locker would be owned and controlled by students. What gets shared. What gets stored. What gets deleted. And yes, perhaps this would mean that the threat that “this will go down on your permanent record” becomes an emptier one.

Too far fetched? Maybe.

But what if education data could not be aggregated or analyzed or tracked or sold without a student’s permission, without their informed consent, without a push notification on their smartphones, perhaps, that someone has accessed their info. How might this shape not just the ownership and control of education data, but students’ ownership and control over their own learning. How might students benefit from this shift?

As it stands, the benefit of much of the data being collected goes to the school or the software provider, but strangely not to the person who created it — to the learner.

And it is, after all, their data, their content, their learning, their data — even if our laws and our policies and our technologies don’t fully recognize it as such. Yet.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the OAuth and OpenID specifications lately. I’ve been thinking about the OAuth and OpenID specifications as an authentication and identity technologies, but honestly almost more like metaphors.

OAuth and OpenID are the open technology standards that allow users to be authenticated with certain websites. OAuth, for example, lets a user grant access to their digital resources on one site to another site. The classic example perhaps: you can sign up for an app using Facebook Connect so that you don’t have to supply a username and password.

Often when developers sketch out these specifications, they’ll represent the exchange of data between the three legs — the platform, the app provider and the user as some describe it, or the server, the client and the resource owner — as an equal relationship. Lots of arrows that map out the requests and the authentication. But it’s almost always drawn as an equilateral triangle or a circle — as though the relationship there between the platform and the application and the end-user is balanced. But it’s not.

Don’t get me wrong. OAuth and OpenID do give the user some control here. It’s not the specifications I’m questioning here. And I don’t want to get into a debate in the Q&A section about the merits of OAuth 2.0.

Rather, I’m questioning how we draw the exchange of data between systems. I want us to think about technologies’ metaphors and their architecture and their power relations — they matter.

It actually makes me incredibly happy to raise these questions — particularly questions about data — here at Webwise. I’ve been trying to raise these questions in a variety of places lately — with university administrators, with K–12 teachers. And while I do want all of us to be more critical about our data collection and data usage, I am particularly keen to raise this issue here with this audience and its professional capacity to think smartly on this topic.

After all, I am thankful for the protests by librarians at laws like the Patriot Act and their ongoing work to protect the privacy and the confidentiality of patrons’ library records. I’m also deeply appreciative of the work that archivists and others here do to think carefully — so carefully — about the preservation of artifacts — digital and otherwise — about the objects themselves and about their metadata. I also value the work that those professions here do regarding open and accessible knowledge, content, data — as well as the challenges of thinking critically about lines between what’s “mine” and what’s “ours.” These are all incredibly important insights that those working in education and in education technology need to learn from.

And I would hope that as we move forward in our more digital, data-oriented world, that questions surrounding the ownership of learners’ data — the centrality of the learner in these and all our discussions — is something that this group can tackle.

“Whose data is it?” “Whose learning is it anyway?” — it’s the learners’, right? But it’s also, at some point, the communities’ — learning isn’t simply about the individual; it’s tied to the greater public good.

And as we move forward building more systems that capture and store and analyze learners’ data, how do we make sure we do so in such a way that the value isn’t extracted from the learner or from the community — trapped in a technological silo, mined simply for corporate profit — but that creates more value — real-time value and long-lasting value.

I would hope that when we ask the question “whose learning is it anyway?” — and with a nod to TV improv too — that we can do so with a smile and not with horror, that we can think of human beings enhanced by technology and not just surveilled or mined or driven by it.

Thank you.

Hack Education Weekly News: "Stealing School," SXSWedu, and News Corp's Education Tablet

Law and Politics

Tanya McDowell, a Connecticut mother accused of fraudulently enrolling her child in a Norwalk school, plead guilty in court this week and was sentenced to 12 years in prison. (She was also charged with drug possession.) McDowell, who was homeless at the time, used a babysitter’s address to enroll her son in school — guilty of parenting while homeless, poor and Black, I guess.

AFT leader Randi Weingarten was arrested this week while demonstrating against the closure of 23 public schools in Philadelphia. The state of education politics in Philly right now is incredibly grim. Have a look at the contract proposals for teachers— pay cuts; benefits cuts; the end to seniority; no more pay increases for continuing education; no more parking spots, teachers’ desks, or water fountains; no more school counselors, and no limits to class sizes.

Edwin Mellen Press said that it will drop the libel lawsuit that it had filed against a university librarian, stemming from a critical blog post he wrote about the publisher. Before we celebrate too much: there is a second lawsuit against the librarian, McMasters University's Dale Askey, based on blog comments. (More details via The Chronicle of Higher Education.)

Last week, I pointed to the news that a piece of legislation in Massachusetts was poised to outlaw data-mining of students’ educational records for commercial purposes. “Sounds like it’s aimed at Google,” I wrote. So no big shock this week when we learned that one of the backers of the law is Microsoft, who’ve been using the “Google reads your email” scare tactic as part of its marketing for a long long time now.

More news in the ongoing legal battle between the textbook startup Boundless and the publishers suing it for copyright infringement. This week, Boundless filed more papers this week, asking the court to dismiss the claims, stating that the startup has revised its product offerings and no longer offers those that the publishers claimed were infringing. (In January, Boundless also sought to have some of the charges against it dismissed.) Inside Higher Ed has a more in-depth look at the case.

In an effort to counter “corporate-style reform,” education historian Diane Ravitch (along with 7 other education leaders) has launched a new education advocacy group called the Network for Public Education. Among its goals: “we will support candidates who oppose high-stakes testing, mass school closures, the privatization of our public schools and the outsourcing of its core functions to for-profit corporations.”

Launches and Updates

Amplify, the education wing of Rupert Murdoch-owned News Corp, unveiled its new tablet this week, with a price starting at $299 (plus an annual subscription fee). According to the USA Today, “Amplify will give teachers the ability to both monitor and control what students do with the device. Teachers can conduct lessons with an entire class or small group and can instantly see what websites or lesson areas students are visiting. A teacher dashboard allows them to take instant polls, ask kids to ‘raise their hands’ virtually and, if things get out of hand, redirect the entire class with an ‘Eyes on Teacher’ button that instantly pushes the message out to every screen.” Well that just sounds completely god-awful, which might explain why no one from Amplify reached out to me on the news or offered me a demo of the product. (Um, among other reasons, I imagine.)

The Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, which launched a data standards initiative Ed-Fi in 2011, announced this week that it was spinning that off into a subsidiary non-profit, the Ed-Fi Alliance, all in the service of supporting Ed-Fi to become the de-facto data standard (or in the service of “better student outcomes,” I suppose, depending on if you cite the press release).

Google released an update to its Google Course Builder (MOOC) platform. The big change: you can now work on your course in the browser.

Skypeannounced at SXSWedu that it was making Group Video Calling available to teachers free of charge. (This feature is otherwise only available as a premium add-on to Skype’s VOIP service).

Testing

The state of New Yorksays that it will not use Pearson as the provider of the high school GED exam. Instead, it plans to use its own which will be developed by McGraw-Hill. Pearson won the contract to offer the GED (previously offered by the non-profit ACE) and plans to hike the prices (to more than double the current cost) and will also charge students for each time they need to retake it.

Obligatory Section on MOOC-Related Stuff

The British MOOC platform Futurelearn announced a partnership with the British Council, an organization that works to promote educational opportunities. The announcement was made while officials were visiting the Middle East, much like the announcement about its expansion last month that was made while officials were visiting India. But don’t worry, MOOCs aren’t about colonization and imperialism at all! Right, Thomas Friedman? Oh… wait…

Cornell plans to run a MOOC based on its popular “Six Pretty Good Books: Explorations in Social Science” class. The class will be funded by a grant from Google and will run on the Google Course Builder technology.

Funding and Acquisitions

The digital portfolio startup Pathbrite announced that it has raised $4 million in funding, in a round of investment led by ACT.

The social networking platform Edmodo has acquiredRoot–1, a startup that’s been building an adaptive learning technology. This is a big win for Edmodo as the Root–1 team are incredibly smart and have a lot of experience in ed-tech. (Two of Root–1’s co-founders, Manish Kothari and Ketan Kothari, were also co-founders of AlphaSmart.) The Kothari brothers, along with Root–1 co-founders Vibhu Mittal and Adam Stepinski, will all move into key roles in Edmodo’s product, research, and engineering teams.

My new pick for the education startup with the worst name, Scoot & Doodle, announced that it has raised $2.25 million in seed funding from “unnamed Silicon Valley angels” and from Pearson.

Slate Science launched a new iOS app called SlateMath K–1 and announced that it has raised $1.1 million in seed funding.

Hellos and Goodbyes

Dan Cohen, the Director of the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University, will be stepping down to take on the role as the executive director of the new Digital Public Library of America. The DPLA is an effort to create, just as the name suggests, a large-scale digital public library available to everyone.

Kushal Chakrabarti, the founder of the education micro-student loan startup Vittana, is stepping down from his role as CEO. There are a lot of education startups that talk a good game about making the world a better place. Vittana actually does that. Best of luck, Kushal. You rock.

Rafael Corrales, one of the co-founders of LearnBoost— one of my favorite education startups, in part for its kick-ass technology and design (I chose it as one of the best startups of 2010 when I still wrote for ReadWriteWeb) — is stepping down and joining a VC firm. This news just breaks my heart, and I plan to write more about this later today…

Conferences and Competitions

SXSWedu ran this week. (You can read my thoughts on the festival here.) No surprise, there were lots of coordinated project launches and promotions. Among the events, the LaunchEDU startup competition. The winners this year were Clever (one of my picks for the top education startups of 2012) and SpeakingPal.

The Times Higher Education World University rankings have been released. Word on the streets: if you’re not in the top 10, you’re doomed! DOOMED!

Photo credits: Audrey Watters

"And This Is Why We Can't Have Nice Things..."

On Loving (and Leaving) LearnBoost

Rafael Corrales, co-founder and CEO of one of my favorite education technology startups, LearnBoost, recently announced that he has stepped down from the helm of the company and has moved on to join a venture capital firm.

I admit: I’m fairly devastated by this news.

I have long been a supporter of LearnBoost, first covering its official launch back in August 2010 when I was still a tech blogger for ReadWriteWeb. There I covered many of the startup’s tech and product updates — including, for example, the development and open-sourcing of its crowdsourced translation interface— even though the editors were always quick to tell me not to cover ed-tech startups. (“Nobody cares, Audrey.”)

Nevertheless, when I was assigned to write the end-of-year story “Top 10 Startups of 2010,” I put LearnBoost on the list alongside other exciting new startups from the year, including Instagram, Flipboard, Quora, Square, and Hipmunk.

I put LearnBoost on the list because, sure, it was an ed-tech startup (Um, hello… people care.). But I wouldn’t have included it if the product and the tech “under the hood” weren’t so damn slick. I put a lot of thought into choosing “the top” startups of any given year; looking back, I stand by the 2010 “top 10 list” — it’s particularly interesting to think about what’s happened to all those on it in the 3 years since.

Looking Back/Looking Forward

LearnBoost launched at the beginning of this recent resurgence in ed-tech entrepreneurialism, and in many ways, I thought it encapsulated much of the promise that new ed-tech startups are supposed to hold: great technology, great product, great team, grassroots adoption, freemium pricing, and so on.

To me, Corrales’ departure now serves to highlight some of the serious tensions, if not grave problems, that this new “ed-tech ecosystem” is facing. Indeed, what sort of “ed-tech ecosystem” are we really building here? Will it thrive? Which startups will survive? Whose values does this “ecosystem” reflect?

On VC-Backed Companies and Expectations for Growth: What happens when a startup raises venture capital? What happens when it raises a little bit of capital (e.g. LearnBoost)? What happens when it raises a lot (e.g. Edmodo)? Do the expectations of investors — for growth, for revenue, for a “return on investment” and for the timeline in which that will happen — match the needs of education (particularly public education) (e.g. Coursera)? Are investors looking at the right signals (growth in signups versus, say, intellectual growth of users)? Can venture-backed startups build long-term, sustainable, non-exploitative businesses in education? Or is “the exit” always on the horizon once VCs get involved?